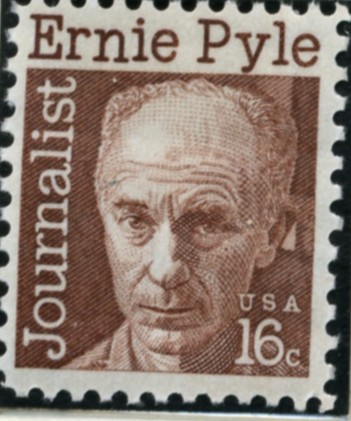

[Seventy years ago, the famous reporter and columnist Ernie Pyle was killed. Walt Tuttle took a side trip to visit the site, on a small island near Okinawa.]

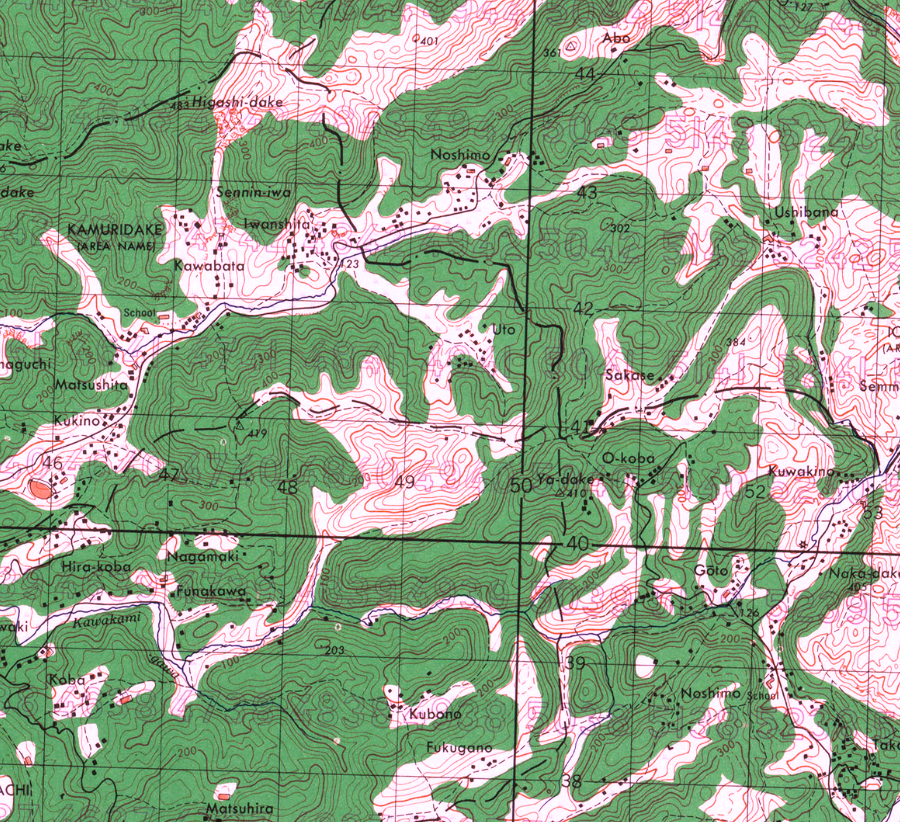

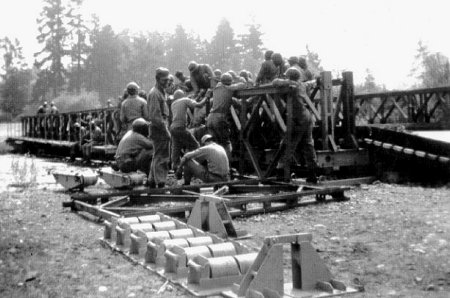

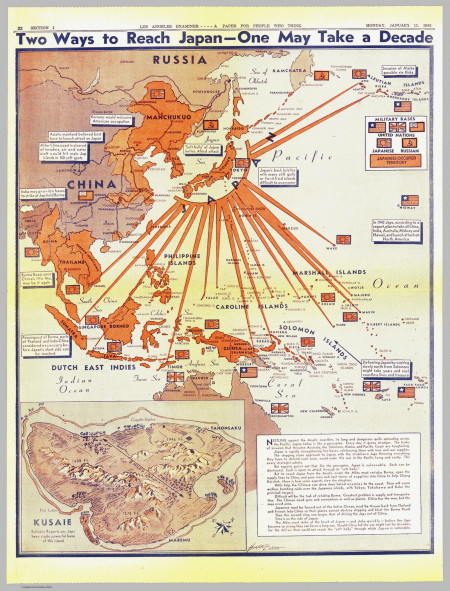

I took my last chance to finish up an important bit of business before leaving Okinawa. Thankfully it was no trouble finding a ride over to the small island of Ie Shima, just west of northern Okinawa. We have small ships shuttling men to and from every occupied bit of dry rock as combat units form up and garrison troops take their places.

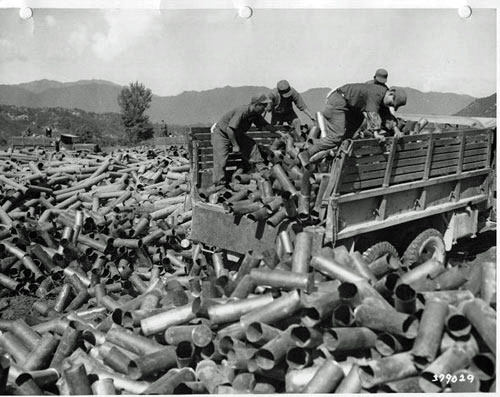

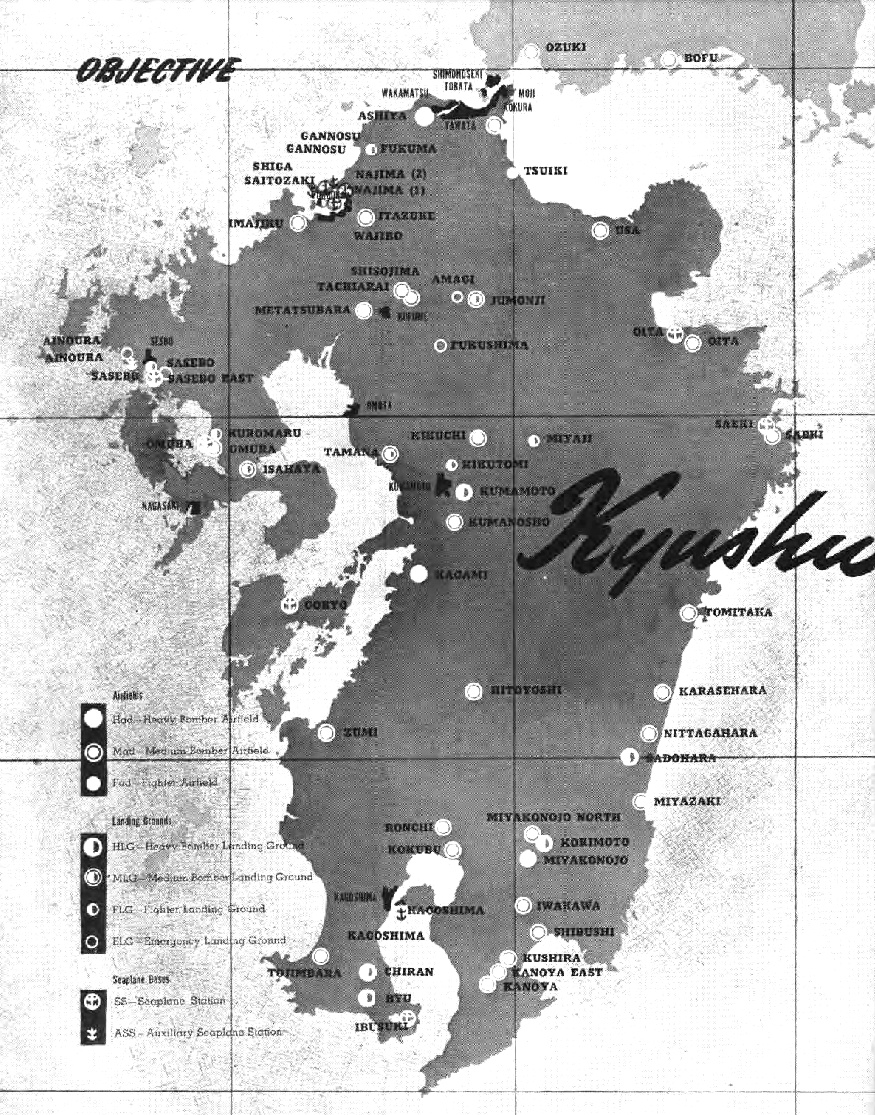

I wanted to visit Ie Shima for a particular, perhaps peculiar, reason. It is a small island with a small mountain and a small airfield, which the Army took with some cost, and many more Japanese died defending it. The same can be said now for many dozens of small islands in the Pacific. Ernie Pyle died here.

If you are reading this column you are probably aware of Ernie Pyle’s enormous legacy. If you are reading this column instead of his, you probably also miss him. I read that Pyle was read in over 700 newspapers, of his own employer’s and through syndication, by 40 million people. I’ve no way of researching the point right now, but I can’t imagine a writer in the past has ever had so wide a circulation or readership. And that at this time when newspapers may be just past their peak of power, as newsreels and radio broadcast news are taking a growing share of attention. Pyle may go down as the most widely read reporter and one of the most influential men of his day. Pyle would have wanted nothing to do with any such power.

Pyle would have wanted nothing to do with any such power.

Pyle made his name by learning about Americans, down on the ground with them, and sharing their stories. Tire treads and shoe leather were never spared as he criss-crossed the continent finding the big little stories that make us up. There was really nothing different about doing that on other war-infested continents. The subjects were living in the ground and getting shot at, but they were living just the same, each with an American story to share.

If you’ve ever felt empathy for a dirty cold soldier 5000 miles away, where you could really feel the chill in your bones as you reflexively scrunch your own shoulders to shrink down into a hole in the earth to hide from exploding artillery shells, it was probably because of Ernie Pyle. If you’ve felt the anxiety of an air base ground crew counting their damaged planes coming back from a raid, and the empty gut that comes when the count is short, it was probably because of Ernie Pyle.

I met Ernie on a number of occasions, but only briefly. A couple times we actually coordinated our activities, to make sure we were in different places and not in with the same type of unit (The Army usually tried to keep journalists from being bunched up in one spot anyway). He wasn’t actually as unkempt in the field as he made out in his writing. Personal grooming and housekeeping in a combat area are tough, as he explained, but people do manage to make a suitable home for themselves wherever they are.

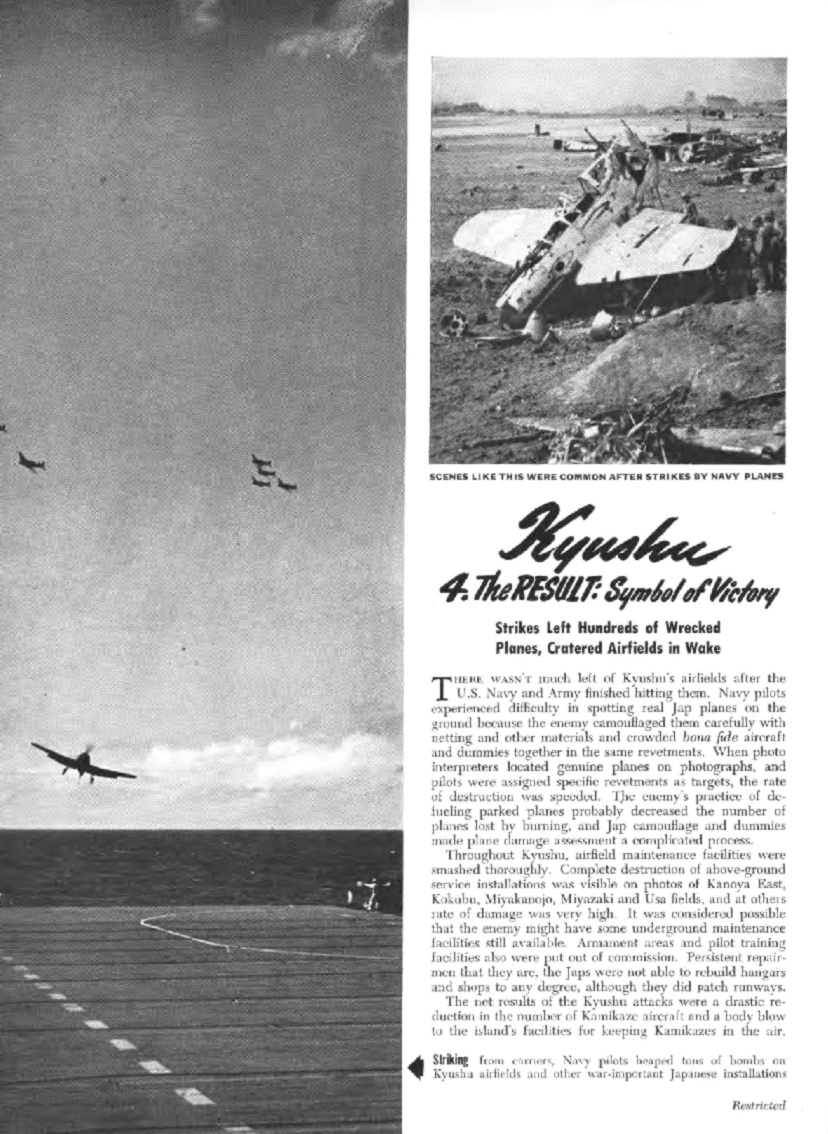

Here on this small island, which will fade again to anonymity once there are not fighter planes operating from its hard-won air strip, Ernie Pyle was in his usual place up near the front lines. Except the lines aren’t so sharp in this desperate fight. The Japanese have employed many tactics to mingle with Americans, to inflict damage on the invaders where our heavy artillery and air power can’t be brought to bear.

In this case a single machine gunner hid out until the American lines went by. He had a good spot. After Pyle’s jeep was attacked, it took a squad all afternoon to flush out the position. A simple wooden marker shows the spot where a well aimed burst killed Ernie instantly.

I will share one of my favorite Ernie Pyle stories, in case you missed it and just because it’s about my adopted southern homeland. Pyle was in Italy with a regiment drawn almost entirely from Tennessee and the Carolinas. The whole unit got paid, in cash, before leaving New York, collecting envelopes worth about $52,000 dollars. After a transatlantic voyage worth of poker games, in England that unit traded in their cash for $67,000 dollars of campaign currency. “Dumb, these hillbillies,” was Pyle’s dry wry end to the story.

[We are happy to report that Ernie Pyle is not forgotten. Indiana University keeps alive the memory of one of her favorite alumni. Any visitor who wishes can sit across from a bronze statue of Ernie and get all the latest scoop.]

Pyle would have wanted nothing to do with any such power.

Pyle would have wanted nothing to do with any such power.