“What was that?

– blind girl, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, July16, 1945

The 75th anniversary of the Normandy D-day is upon us. While that D-day and the many D-days of the Pacific war are front of mind, X-Day: Japan is on sale! Look for eBook and paperback specials to add to your library or to present a summertime gift.

“Okinawa is about 5 miles across in its southern portion where we had four divisions abreast fighting stiff resistance for two months to advance about 15 miles, taking casualties all the way. Southern Kyushu is 90 miles wide, and we plan to land maybe 13 divisions. That would spread forces out almost six times as thin. Total area to be taken is well over 5,000 square miles. They talk about having ‘maneuver room’ and ‘flexible force concentration’ to overcome this. Time will tell. “

[Not included in the original Kyushu Diary, this Tuttle column is often reprinted on Chirstmas Eve. We share it this week marking the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor.]

I made reference back on the 7th to the Pearl Harbor attack of 1941. For me this date, December 24th, Christmas eve, will always remind me more of that horrible fateful day. Because the destruction from the attack didn’t end on the 7th. One story of loss will stick with me. On December 8th tapping was heard from deep inside the partially sunk battleship West Virginia, where some number of men were trapped deep below deck. On December 24, 1941, the tapping stopped.

The West Virginia is here with us now, along with four of her sister ships from Pearl Harbor’s now infamous ‘Battleship Row.’ The trouble with sinking ships in a harbor, especially Pearl, is that you can’t. It’s too shallow. Big ships settle on the bottom, still half above the surface, and a good harbor has every facility one would want to patch up and re-float the ships. In fact the Nevada, the only big ship to get under way that morning, was deliberately grounded after she took damage so she could be recovered and repaired.

The hit at Pearl was a big one for sure, and permanent for thousands of young servicemen, but for most of the big ships ultimately only temporary. Certainly Japanese planners knew this going in. The U.S. Pacific Fleet was mighty thin for the next year, reduced to hit-and-run harassing strikes with the carriers that by luck weren’t there in Hawaii. But since then, with scores of new and repaired (and upgraded) big ships joining the fleet, it has leapfrogged the worst nightmares of those admirals in Tokyo.

Much has been said about fast aircraft carriers taking over from the battleships of old as kings of the sea. That may well be true on the ocean, where fleets have engaged in air duels well out of gun range many times across the Pacific. But here on dry land, I can certify that the battleship is very much respected, or feared, depending on which side you’re on.

Navy ships sail with bigger guns than any army even attempts to drag along on land. Any place on the Earth within twenty miles of forty foot deep water can be blasted by one ton shells from our newest big ships. Japan is an island nation, and all of her conquests outside of China have been more smaller and smaller islands. All of them are vulnerable to the wrath of naval ordnance over almost all of their surface. Planes could drop bombs of the same size, but low flying planes can be shot down with the smallest of anti-aircraft guns. The only defense against navy guns available to most Japanese garrisons has been to dig and dig and dig, deep down into the rock if they can, and wait to be flushed out by flame throwers once the Army or Marines land under the support of those big old battlewagons.

Here on Kyushu, we found the main beach defenses lined up just exactly beyond the range of most navy guns. At Ariake there were the reverse-slope positions our Navy couldn’t get at until sailing into the bay, and that cost us something. But outside of that, the best tactic the Japanese had was to leave old guns in dummy installations near the shore to soak up shell fire.

The ships that came back from the knock-down at Pearl Harbor were mostly older slower vessels, but they work just fine for work along the shore. Islands don’t move very fast after all. The battleships have been kept very busy. The USS New York just rejoined the fleet after having her guns re-lined. They were worn out from firing so many thousands of big shells at Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Back to the story of the West Virginia. Re-floating a damaged ship does take some time. She didn’t make it into dry-dock for repairs until June 18, 1942. Before that many attempts were made by divers and search teams to enter the lower compartments and rescue survivors or recover bodies. That is also necessarily slow work. Cutting into a closed compartment will flood it, and possibly many more compartments if the hatches aren’t all closed. Letting a lot of air out and water in can destabilize the whole ship, sending it over and ruining all chances of rescue or recovery.

I have it on good authority, but off the record, that three young men were recovered from the last compartment opened on the West Virginia. By match light they had marked off the days on a calendar through December 23rd. The Navy has decided never to identify them. They will be officially listed as Killed-In-Action, December 7, 1941.

[History repeats itself, sometimes only months apart.]

I entered one important looking tent and found staff officers huddled over local maps, noting positions of subordinate units and updating strength and supply tables for each. More senior officers were working around a smaller table. They had laid out another map, not of Kyushu, but of southern Okinawa. I was familiar with the area, from watching men train there. These officers knew it better, from watching men die there.

The 77th and the 81st infantry divisions had yesterday been repulsed, with tough losses. They were trying to jump from one line of anonymous hills and high paths over onto a larger set of named peaks and ridges. The 77th had tried the same thing on a smaller scale on Okinawa and also failed on the first several attempts.

Dead and injured were still being collected from yesterday, but the new attack would not wait. They were to go again this morning, with a new plan based on old lessons. Rain was predicted to continue for a third day, but that too was just like on Okinawa.

The Navy was called in to Kagoshima Bay to support with big guns. Once the attack started they would not fire on the mountainsides which our soldiers were attacking. They would plaster the reverse slopes, where it was expected Japanese defenders were only shallowly dug in. So long as they stayed hunkered down, American teams could work methodically through the valley between the two high lines.

Noise of the renewed assault was thick and loud by the time I went up with an observer from the headquarters unit. Engineers had worked through the last two days and nights to clear rough roads through and over the forested hills. Softer parts of the road were corduroyed with felled logs, brutal riding in a round-wheeled jeep. We came out onto one of the sharper peaks, dodging a hard working bulldozer to make the top.

Heavy tanks and larger self-propelled guns had been established on most such local peaks, owing much to extreme engineering effort. More than one had been left stuck, or had simply fallen right through the edge off of a waterlogged embankment.

Our tanks would be static guns for the day. They could depress their guns better than the heavy howitzers, firing directly down into the valley. Down in that valley mixed teams of tanks and liberally equipped infantry worked along the valley at a dead slow pace. They could rarely be seen.

Usually we could only track American progress by the smoke and dust made by their magnanimous application of firepower. When one of the smaller tanks came forward, there was no mistaking the sight of its long range flame thrower scorching a substantial patch of the mountain.

The opposing ridge was rugged and wavy, with many deep crevices in the near side. Each crevice was treated as a new objective, soldiers climbing up the near edge, before tanks turned into it as the men moved around the edge. Steady rain kept visibility short and footing haphazard.

Japanese guns waited for good targets and opened up only when the side of a tank or a cluster of men presented themselves, which was often. The Japs took a toll on the approaching soldiers and armor, often firing from close range where the covering guns on our side of the valley could not safely engage them. More than once the American GIs simply backed up and waited for friendly guns to pulverize the threat, before rushing the position with grenades and charges.

I made reference back on the 7th to the Pearl Harbor attack of 1941. For me this date, December 24th, Christmas eve, will always remind me more of that horrible fateful day. Because the destruction from the attack didn’t end on the 7th. One story of loss will stick with me. On December 8th tapping was heard from deep inside the partially sunk battleship West Virginia, where some number of men were trapped deep below deck. On December 24, 1941, the tapping stopped.

The West Virginia is here with us now, along with four of her sister ships from Pearl Harbor’s now infamous ‘Battleship Row.’ The trouble with sinking ships in a harbor, especially Pearl, is that you can’t. It’s too shallow. Big ships settle on the bottom, still half above the surface, and a good harbor has every facility one would want to patch up and re-float the ships. In fact the Nevada, the only big ship to get under way that morning, was deliberately grounded after she took damage so she could be recovered and repaired.

The hit at Pearl was a big one for sure, and permanent for thousands of young servicemen, but for most of the big ships ultimately only temporary. Certainly Japanese planners knew this going in. The U.S. Pacific Fleet was mighty thin for the next year, reduced to hit-and-run harassing strikes with the carriers that by luck weren’t there in Hawaii. But since then, with scores of new and repaired (and upgraded) big ships joining the fleet, it has leapfrogged the worst nightmares of those admirals in Tokyo.

The ships that came back from the knock-down at Pearl Harbor were mostly older slower vessels, but they work just fine for work along the shore. Islands don’t move very fast after all. The battleships have been kept very busy. The USS New York just rejoined the fleet after having her guns re-lined. They were worn out from firing so many thousands of big shells at Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Back to the story of the West Virginia. Re-floating a damaged ship does take some time. She didn’t make it into dry-dock for repairs until June 18, 1942. Before that many attempts were made by divers and search teams to enter the lower compartments and rescue survivors or recover bodies. That is also necessarily slow work. Cutting into a closed compartment will flood it, and possibly many more compartments if the hatches aren’t all closed. Letting a lot of air out and water in can destabilize the whole ship, sending it over and ruining all chances of rescue or recovery.

I have it on good authority, but off the record, that three young men were recovered from the last compartment opened on the West Virginia. By match light they had marked off the days on a calendar through December 23rd. The Navy has decided never to identify them. They will be officially listed as Killed-In-Action, December 7, 1941.

[Tuttle was keen to include textbook details of tactics from the better small infantry units he saw.]

Charlie Company, 3rd Battalion, 188th Glider Infantry Regiment, 11th Airborne Division, welcomed me in to their un-named hilltop HQ. The artillery behind them had rated hill “number 260.” This unit would not have a named home until they took a taller hill across the valley, hill “number 367.”

Company CO Captain Arthur Leonard told me a bit about the trip forward. “We practically hiked straight in. We took up old positions the 162nd [Infantry Regiment] held and then another couple hills past that.” He pointed back up to the mortar squad behind them that I passed on the way. “The Japs had pulled out. All we saw were two snipers, and we’re still looking for booby traps here.” He drew a wide circle around the camp which had been a Japanese infantry camp facing the other direction. Captain Leonard said the land here isn’t too different from where he used to hunt in the Alleghenys east of Pittsburgh.

Platoon Sergeant Walter Strauss, also of Pennsylvania but more accustomed to the flat Erie lake shore, was standing next to us and pointed out the sandbag berms his men were set behind. “We even got to reuse the Jap sand bags. Except they left grenades jammed under some of them.” That drew a couple chuckles from some shovel-hefting enlisted men, even though the first grenade caused two casualties. “I’ve sent back three medical cases so far,” the captain explained. “One of them was a bit of grenade shrapnel in a guy’s butt, but another was a twisted ankle his buddy got diving from the grenade. He tumbled straight down the steep end of the hill, arms swinging like he was swatting off bees.”

The unit was digging in for the night. Some gentle encouragement from the sergeants was required to get the holes textbook deep, as they had yet seen no enemy soldiers nor any artillery rounds. I had drawn a bedroll and extra blanket to camp under as winter weather was finally being felt on the temperate island. With clear skies the temperature would get below 50 and stay there until the sun made its brief appearance the next short day.

Artillery was heard that night, to either side of us, less than two miles away. They were short barrages, but of heavy caliber from far away. We never heard the sound of the launch, which would have followed some seconds after the report of the exploding shells in the passes east and west of us. Some small villages sat in the river valleys that made up each pass, but all were deserted save for a few American sentries.

Before dawn the third watch roused everyone and men fumbled to gather their gear under a moonless sky. At the pre-appointed time, artillery and mortars from several distances behind us began their almost daily ritual. Flashes of light walked up the hillside opposite us, and on many other faces up and down the American line. When we couldn’t see the flashes any more, the explosions were on the back sides of the objective hills, and it was time to move out.

The company advanced in two waves of squad columns, in a chevron formation. At least that’s what the captain told me it was. I went out behind the second wave in any case. The next peak was about three-quarters of a mile away, but we had to go down about two hundred feet and up three hundred to get to it. Our side was a single slope, but the opposite side was broken and wavy.

We had some light by then. Groups of men moved in and out of the remaining clusters of trees. Previous artillery fire had roughly cleared deliberate sight lines, which were good for us to spot the moving enemy, but of course they work both ways. Half charred felled trees were a nuisance everywhere.

A half hour passed before the first shots were fired. A few rifle shots went up into trees that could hide a lurking sniper, but a submachine gun was preferred to rake the tree tops. Forty minutes of careful hiking, two or three stumbling steps down, followed by a rifle-ready scan of the opposing hill, had the front wave at the bottom of our hill. Runners reported adjacent companies all on track and no trouble to the sides. The lead squads advanced again, up the next hill.

Columns drifted apart some in the twisted terrain, and lieutenants made adjustments to keep us lined up and to cover blind spots. The point of the advance was moving directly toward the crest of “hill 367,” groups of men trailing it left and right in a vee. They paused at the last trees before a clearing at the top, letting the line come up more even. Then the whole line moved forward over the top.

[Not a field report, but included in Kyushu Diary, Tuttle gave readers an overview of the American battle plan.]

The primary focus of operations at the end of 1945 was to get as many troops as available onto Kyushu before winter set in. The troops available would be all the Army divisions MacArthur had used in the Philippines, and whichever Marine corps divisions were not heavily involved on Okinawa, the most recent operation.

Four multi-division army corps were set up, under a general command called the Sixth Army under General Walter Krueger. Planning staffs had labeled over 30 possible landing beaches on the southern third of Kyushu, naming them in alphabetical order from east to west by automobile brands. The final plan had us using eight of them in three clusters for the X-day assault.

The Marine Corps sent its 2nd, 3rd, and 5th divisions as the Fifth Amphibious Corps. They would land on the west coast, south of the city of Sendai. The First Corps, Army divisions 25th, 33rd, and 41st, would land on the east coast, either side of the city of Miyazaki.

South of that in Ariake Bay the 1st Cavalry Division, 43rd Infantry Division, and the Americal Division would land as the Eleventh Corps. Another corps, the Ninth, on X-2 has already made an elaborate fake landing operation toward Shikoku far to the northeast. Its 77th, 81st, and 98th infantry divisions can land as needed later. They are penciled in for a landing south of the Marines on X+3 or X+4. Ninth Corps also had the 112th “Regimental Combat Team” , which could deploy independently. Incidentally, the 98th is an all new unit, the only one here with no combat experience.

Ahead of the multiple corps, the 40th Infantry Division, reinforced with the 158th Regimental Combat Team, started landing on the smaller islands south and west of Kyushu, to eliminate them as threats to the main fleet once it arrived.

What we need out of Kyushu most of all is airbases. You may have noticed, B-29 bombers are not small. They need room to stretch out those long wings, and they prefer wide long runways. In addition, there are supply depots and workshops and barracks for a million men (or more) to build. But Kyushu does not have an abundance of flat land to offer. It is woven from a coarse thread of steep ridges and volcanic peaks, interrupted only briefly by flat valleys and a few small plains. To get enough space for our uses, and secure it from Japanese long range artillery or sneak attack, we plan to push well into the hills north of the last set of valleys.

As a layman looking at all this, the invasion plan at first looked like a focused application of awesome force, and it was impossible to see how such a large and well equipped invader could be turned away. But I had been at this a little while by then, and I did a little calculating. I’m sure real staff officers in many headquarters and Pentagon offices had run the same numbers many times.

Okinawa is about 5 miles across in its southern portion where we had four divisions abreast fighting stiff resistance for two months to advance about 15 miles, taking casualties all the way. Southern Kyushu is 90 miles wide, and we plan to land maybe 13 divisions. That would spread forces out almost six times as thin. Total area to be taken is well over 5,000 square miles. They talk about having ‘maneuver room’ and ‘flexible force concentration’ to overcome this. Time will tell.

[Tuttle explains the name “X-Day” and bemoans the popular presumptions around “D-Day”.]

We are in Fifth Corps (amphibious), with three Marine divisions, the 2nd, 3rd, and 5th. Two other similar size corps, Eleventh and First, will assault the island elsewhere. The augmented 40th Infantry Division is already ahead of us landing on some of the smaller islands off Kyushu. Another whole corps, the Ninth, is staging a feint far to the northeast, and there are an ‘unspecified number of follow-on units.’

So far as I am told, until recently it was U.S. military practice to always call the day of an invasion, amphibious or otherwise, “D-day.” (They also call the hour that it starts “H-hour.”) Something changed in the last year, now that “D-day” has become something of a brand name.

Newspapers take D-Day to mean specifically the June, 1944 expansion of the war against Germany with landings on the Normandy coast of France. They already forget about the other fights which raged even then in all corners of Europe.

If they do that much in a year, I have to wonder what people will be told of this war fifty years from now. There might be just one D-day, which decided the whole fight in Europe. Never mind the massive land war in Russia, the back-and-forth turf wars in north Africa, or the painful struggle through Italy. In a hundred years they may just call it “The D-Day War” .

Anyway, since Normandy and “D-Day” are forever linked in the public mind, the military had to get more creative. For the invasion of Luzon in the Philippines they called it “S-day.” At Okinawa, April 1st, which happened to also be Easter Sunday, was called “Love Day,” much to the chagrin of superstitious or wry-witted soldiers and Marines who saw the setup of a bemusing but possibly bitter irony.

This time around our invasion of the island of Kyushu, set for November 15th, 1945, will begin on “X-day.” That makes today X-4. I for one am glad we are back to a simple single letter.

[Tuttle shuttled over to visit another island off Okinawa while everyone else packed up for the impending invasion.]

I wanted to visit Ie Shima for a particular, perhaps peculiar, reason. It is a small island with a small mountain and a small airfield, which the Army took with some cost, and many more Japanese died defending it. The same can be said now for many dozens of small islands in the Pacific. Ernie Pyle died here.

If you are reading this column you are probably aware of Ernie Pyle’s enormous legacy. If you are reading this column instead of his, you probably also miss him. I read that Pyle was read in over 700 newspapers by 40 million people. I’ve no way of researching the point right now, but I can’t imagine a writer in the past has ever had so wide a circulation or readership. This was at a time when newspapers may be just past their peak of power, as newsreels and radio broadcasts are taking a growing share of attention. Pyle may go down as the most widely read reporter and one of the most influential men of his day. Pyle would have wanted nothing to do with any such power.

Pyle made his name by learning about everyday Americans and sharing their stories. Tire treads and shoe leather were never spared as he criss-crossed the continent finding the big little stories that make us up. There was really nothing different about doing that on other war-infested continents. The subjects were living in the ground and getting shot at, but they were living just the same, each with an American story to share.

If you’ve ever felt empathy for a dirty cold soldier 5000 miles away, where you could really feel the chill in your bones as you reflexively scrunch your own shoulders to shrink down into a hole in the earth to hide from exploding artillery shells, it was probably because of Ernie Pyle. If you’ve felt the anxiety of an air base ground crew counting their damaged planes coming back from a raid, and the empty gut that comes when the count is short, it was probably because of Ernie Pyle.

Today we conclude this series of specific references behind the details in X-Day: Japan. These are not formal citations, as they are not all root sources and the book is not an academic volume. The use of real historical elements for X-Day: Japan serves to educate the reader about the time, add interest to the story, and honestly it just made the thing easier to write!

November 23, 1945

Jumbo air-to-ground rocket,

– airandspace.si.edu

November 27, 1945

1st Cavalry Division,

– first-team.us

December 3, 1945

M29 Weasel,

– m29cweasel.com

December 8, 1945

M26 Pershing tank next to M4 Sherman tank (models),

– warbird-photos.com

December 9, 1945

War Department Technical Manual TM-12-247,

Military Occupational Classification of Enlisted Personnel,

– archive.org

December 10, 1945

U.S. Army Center of Military History style guide,

– history.army.mil

December 11, 1945

Battle Formations – The Rifle Platoon, for NCOs (1942)

– youtube.com

December 21, 1945

Hospitalization and evac plan for Operation Olympic,

Logistic Instructions No. 1 for the Olympic Operation, 25 July 1945

– cgsc.cdmhost.com

USS Sanctuary, hospital ship AH-17

– navsource.org

December 22, 1945

Russian communists vs Chinese communists,

– Tom Clancy, The Bear and the Dragon

Chiang Kai-shek quote on the communists vs the Japanese,

– izquotes.com

December 23, 1945

Sakura-jima and its volcanoes,

– photovolcanica.com

December 25, 1945

USS Hazard, minesweeper AM-240 [MUSEUM SHIP],

– nps.gov

– tripadvisor.com

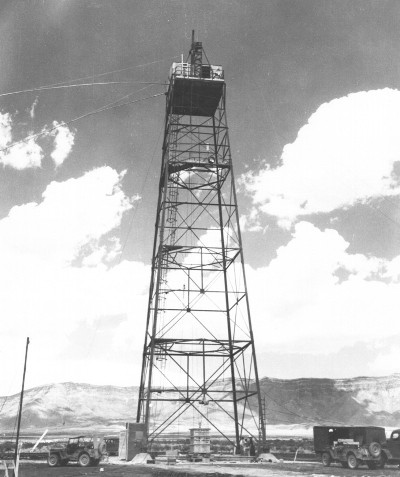

January 17, 1946

Radiation detection equipment,

– national-radiation-instrument-catalog.com

July 18, 1945

PBY-4/5 Catalina flying boat,

– pwencycl.kgbudge.com

Consolidated Aircraft plant in San Diego,

– sandiegohistory.org

Consolidated Aircraft plant production and products, B-24 and PB4Y-2,

– legendsintheirowntime.com

– wikipedia.org

December 24, 1945

Pearl Harbor survivors, trapped under USS West Virginia,

– nps.gov

– community.seattletimes.nwsource.com