[This portion of Tuttle’s entry for November 15 is shared for the occasion of the 71st anniversary of the well known D-Day this week, June 6, 1944. D-Days like at Normandy were routine jobs in the Pacific.]

I don’t like to think that there is anything fundamentally different for the average soldier between preparation for an amphibious invasion and any other long planned attack. The guys who can eat, eat. The guys who can’t eat, give their chow to the other guys. Special church services are held. Gear is checked and re-checked. Blades are sharpened, rifle actions cleaned and oiled. Veterans do whatever they did last time, because it worked. New guys don’t know what to do. Some sing, some sleep, most can’t sleep and just stare at the bunk above them, where the next man is doing the same thing at the bunk above him, until they get to the poor guy on top who has nothing to stare at but the bare gray ceiling.

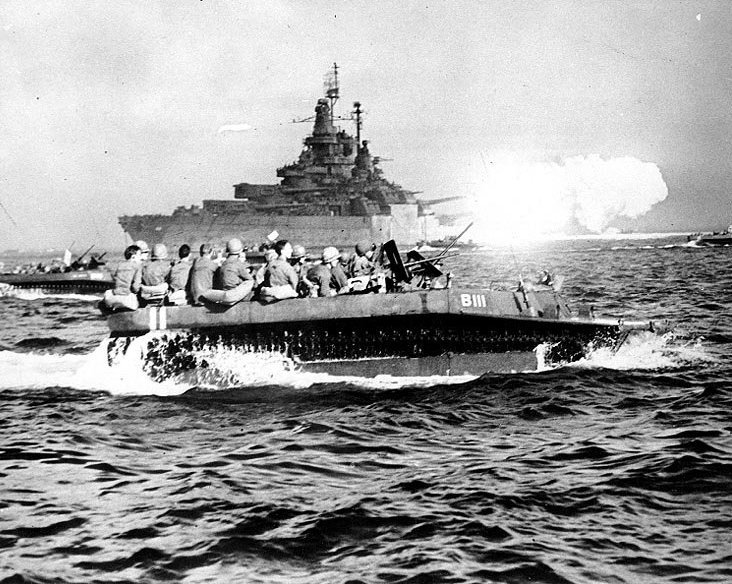

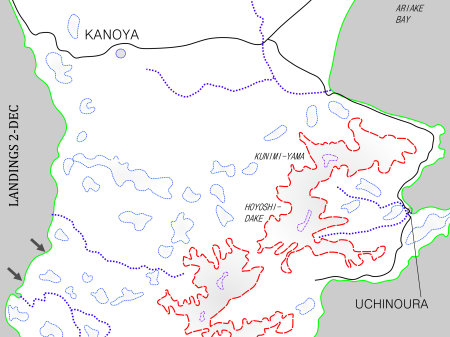

There are mechanical differences between an amphibious operation and an attack over land. For starters, amphibious troops launch miles away from the real starting point. The big ships lay well back from land until the final morning, for their own safety. The troops ordained to go in can’t even see the objective but as a fuzzy line on the horizon until that morning.

In staged battles of old knights and footmen could look directly across the chosen field, and even see smoke from their opponent’s camp fires. Even in the muddy fields of 1917 France, today’s majors and colonels were lieutenants looking through field glasses (or periscopes) directly at the front berms of the enemy trenches.

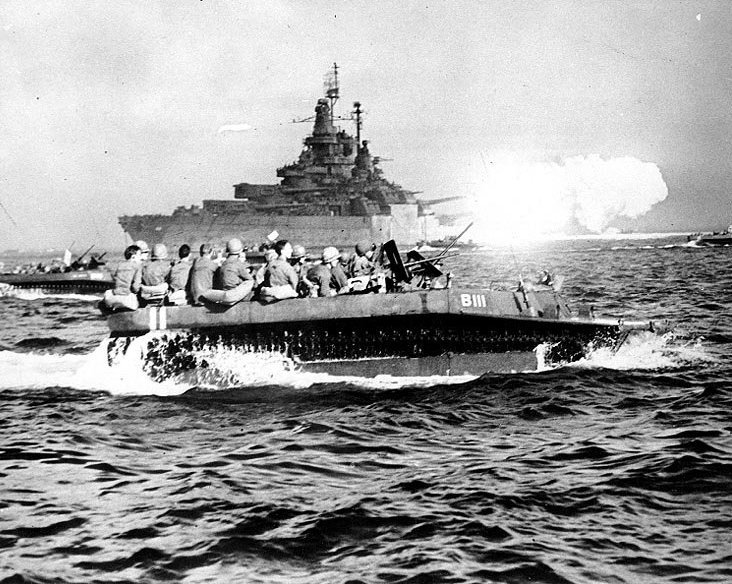

On the way in an amphibious trooper is blind and helpless. There is absolutely nothing to do but crouch down in the assault boat and hope it doesn’t get hit. Or get stuck. Or break down. The soldier has to take it on faith that all the sailors do their jobs and line the boats up right and move them in good order and get them ashore where they are supposed to be.

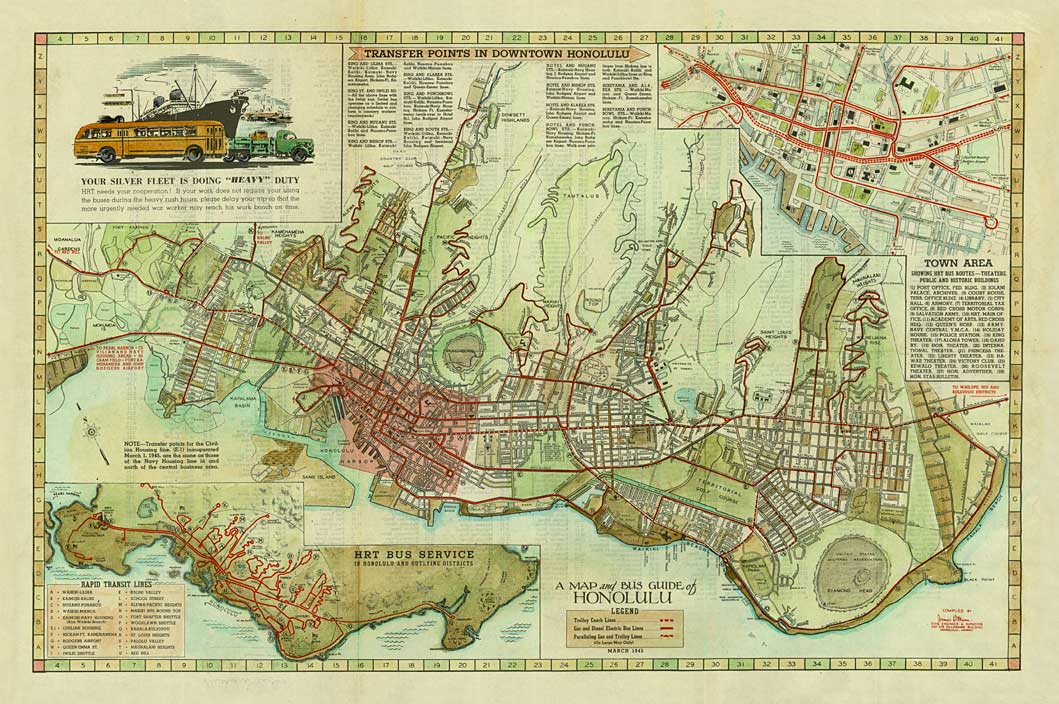

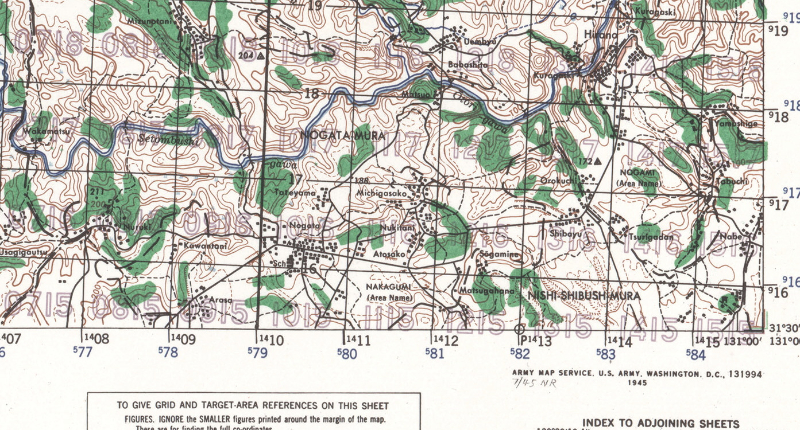

Then the solider has to take it on faith that the reconnaissance was good, that the map is accurate, that the navy divers took out their assigned obstacles, that the naval bombardment hit what it was scheduled to hit, and that the first objectives for his unit are where they are supposed to be. Marching under a flag by trumpet or charging out of a trench the infantry man can see his own unit all the way, and the unit can do what it needs to do to stay organized. The unit is divided and helpless during the approach to a beach.

Incidentally, if terrain like a beach was all dry land and it was in a manual of military tactics, the manual would say “Do not under any circumstances attack here!” On a beach one is attacking uphill, approaching in the open, against prepared defenses on high ground, often with trees and brush covering them. It’s a bad way in, but it’s the only way in when one attacks an island, so this is our lot.

For this assault I’ve set myself among support staff and reserves. No one from this ship is going in on the first day. (They did lower a few of our boats, but I’m told those are just spares.) I’ve been around the nervous tension of men going in with the first wave before. I wanted to see how it is for the other guys.

There’s plenty of nervous tension here. In fact, I think it may be worse. For all the reasons above, the guys going in for the invasion have a sense of resignation to them. There’s nothing they can do about the whole trip in, and to cope with that I think they detach a little. The men here don’t have that. They have their own work to do, from minute zero on, and they all believe lives depend on it. Each man wants to be sure his part goes flawlessly.

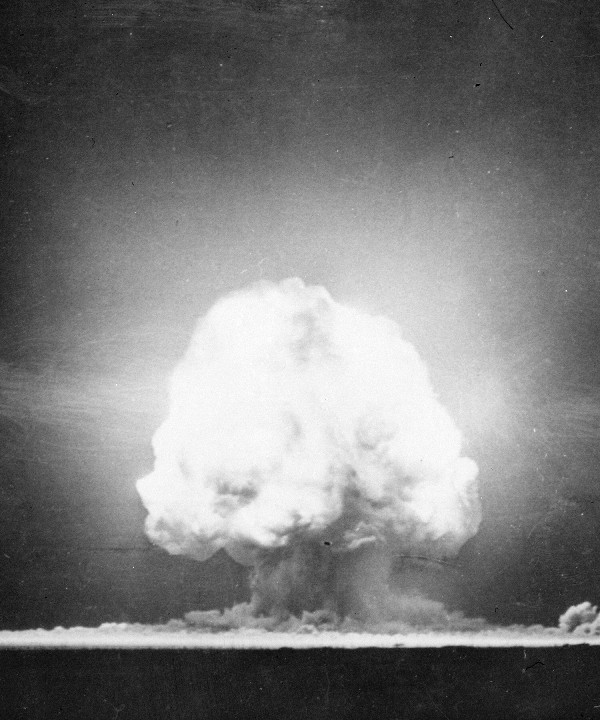

Thing is, there’s not much some of them can do about it either. I found one of the radio men, Ensign Gaston Morton, from Stillwater, Minnesota, studiously memorizing the lists of ships from our invasion flotilla and every other squadron and fleet on this job. “There’s a slim chance I would ever need to relay a call for a destroyer on the far side [of Kyushu], and I could look them up in a minute anyway. But the only other thing I could do right now is clean and polish the vacuum tubes on the radio sets. What about you? What do you do when you’re waiting around to start an important job?”

I’m not used to my interview subjects asking back! I told him that, first of all, I don’t recall ever having a particularly important job to do. But if I did, to pass the time waiting for such a job to start, I would probably go interview someone else about his job.