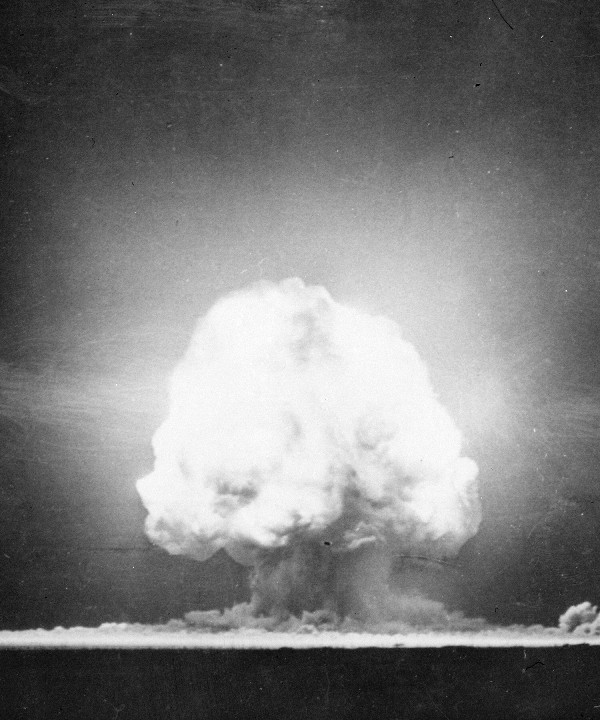

[The following is a portion of Tuttle’s entry for this historic day. He of course had no idea it was the day of the first atomic weapon test in history.]

I spent the afternoon idly shopping in town near the beach. The place is thick with servicemen, enough that the military has MPs out on patrol in addition to the local authorities. The retailers closest to the bases and barracks have adapted to cater to them, carrying supplies, trinkets, and services directly in the interest of a freshly paid solider or sailor. Prices that aren’t regulated are higher than they would be in a place not stuffed full of young men with new money burning holes in their pockets and little time to spend it.

I have my own agenda, which includes finding a new pair of field glasses, as mine got lent to a desperate young officer in France, who I expect kept them in use through a substantial portion of western Germany. I also want to add to my collection of local newspapers. It’s been a great way to make new friends, running a small lending library of home front newspapers.

It doesn’t matter where the it is from, or what size town, guys far away like to catch up on the little things that don’t make it into the news sheets that the military takes care to send forward. A race for county drain commissioner means more to a soldier than world geo-politics. A man in a dirt hole just wants to know that life back home is carrying on as always and waiting for his return.

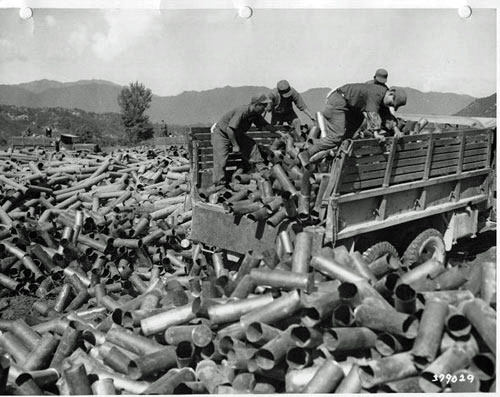

My trip out is probably coming up soon, so I took a last stroll down the boardwalk, stopping in a souvenir stand to get my picture taken with my fake “medal.” After dinner in a crowded soda shop I picked up the photo print, headed back, and dumped the medal in a scrap bin at base – they say we need every bit of loose steel we can get.

Two of the afternoon papers I picked up have an identical short article off the wire about an explosion at an old weapons dump in New Mexico. It was north of Albuquerque, near a small town called Los Alamos. There were some chemical shells, and people are advised to stay away and possibly be ready to evacuate should the winds blow toxic fumes toward town. It’s disturbing to think about what might happen if unconventional weapons get unleashed in what remains of this conflict. They have been treated to undoubted technological development since the so-called “Great War.” I wonder to myself just what horrible weapons might still be unleashed in the fighting to come.

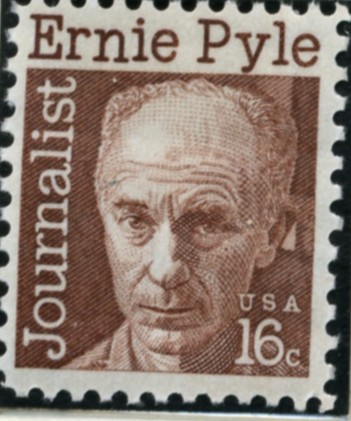

Pyle would have wanted nothing to do with any such power.

Pyle would have wanted nothing to do with any such power.