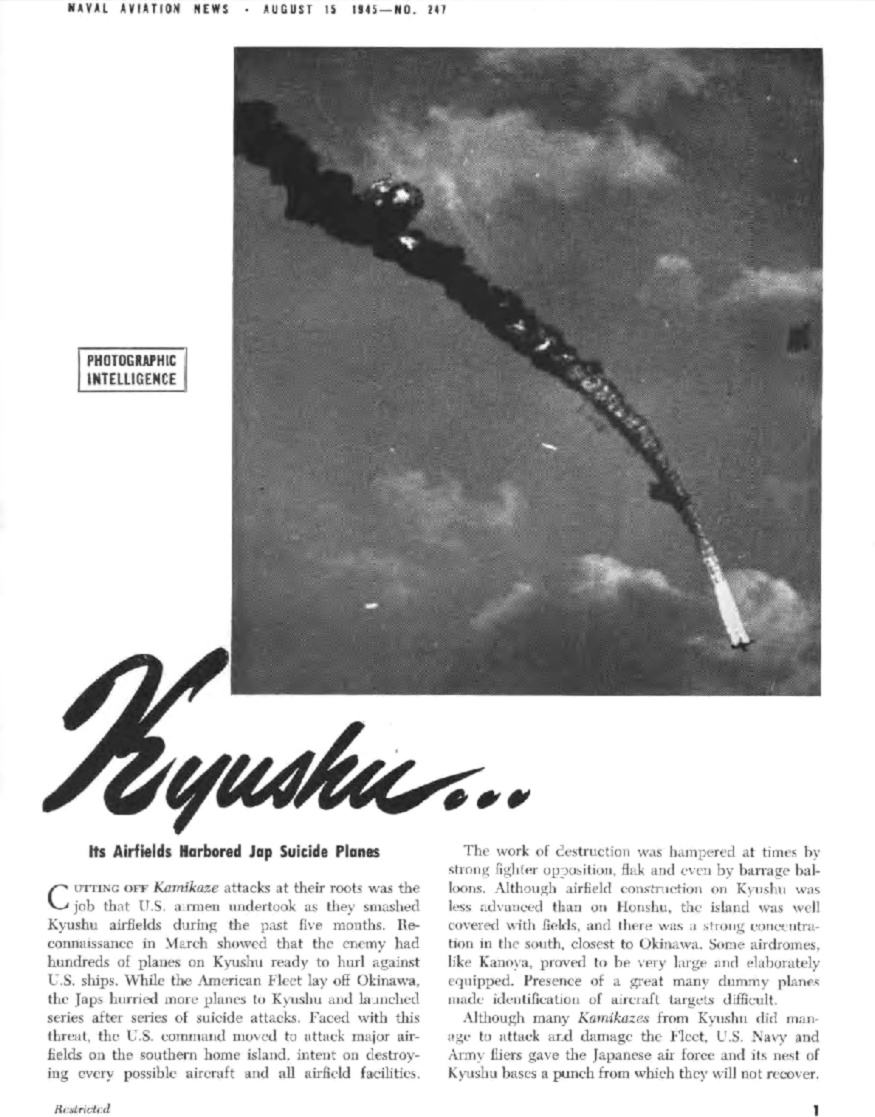

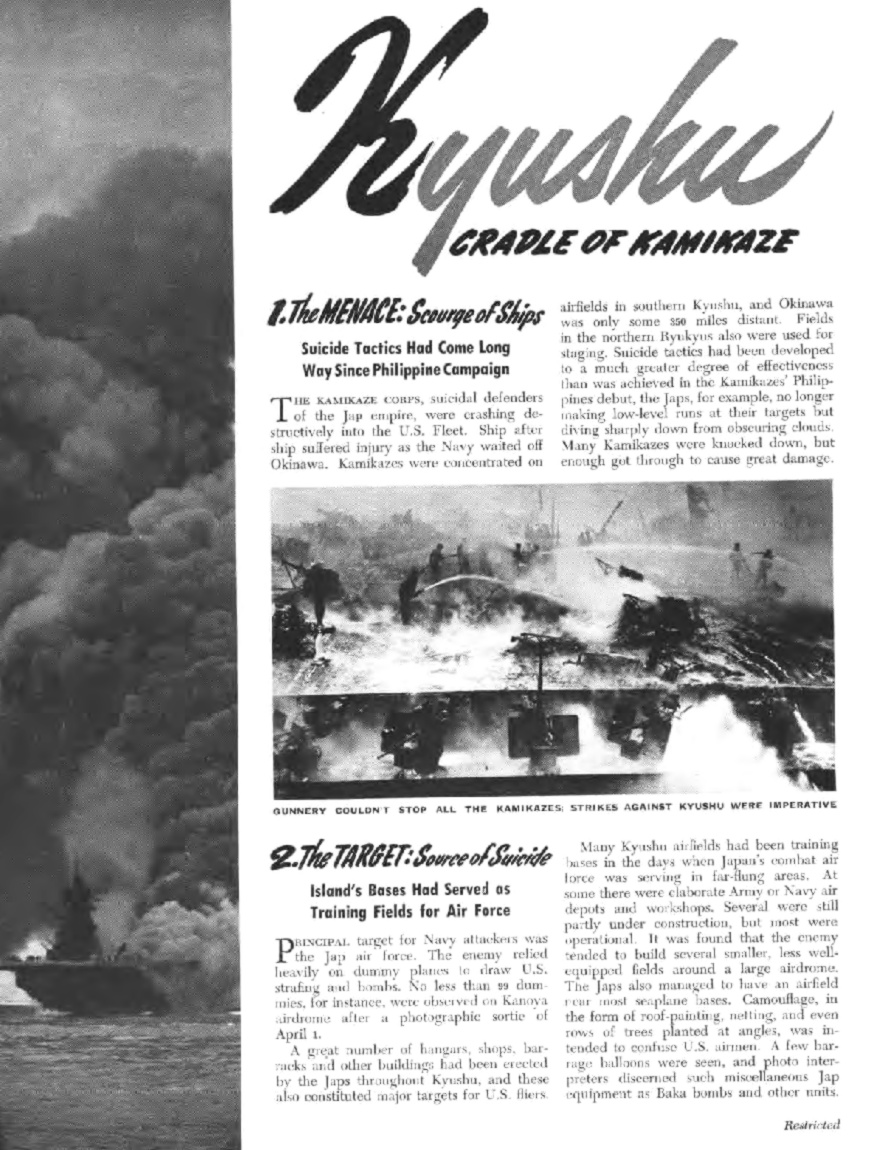

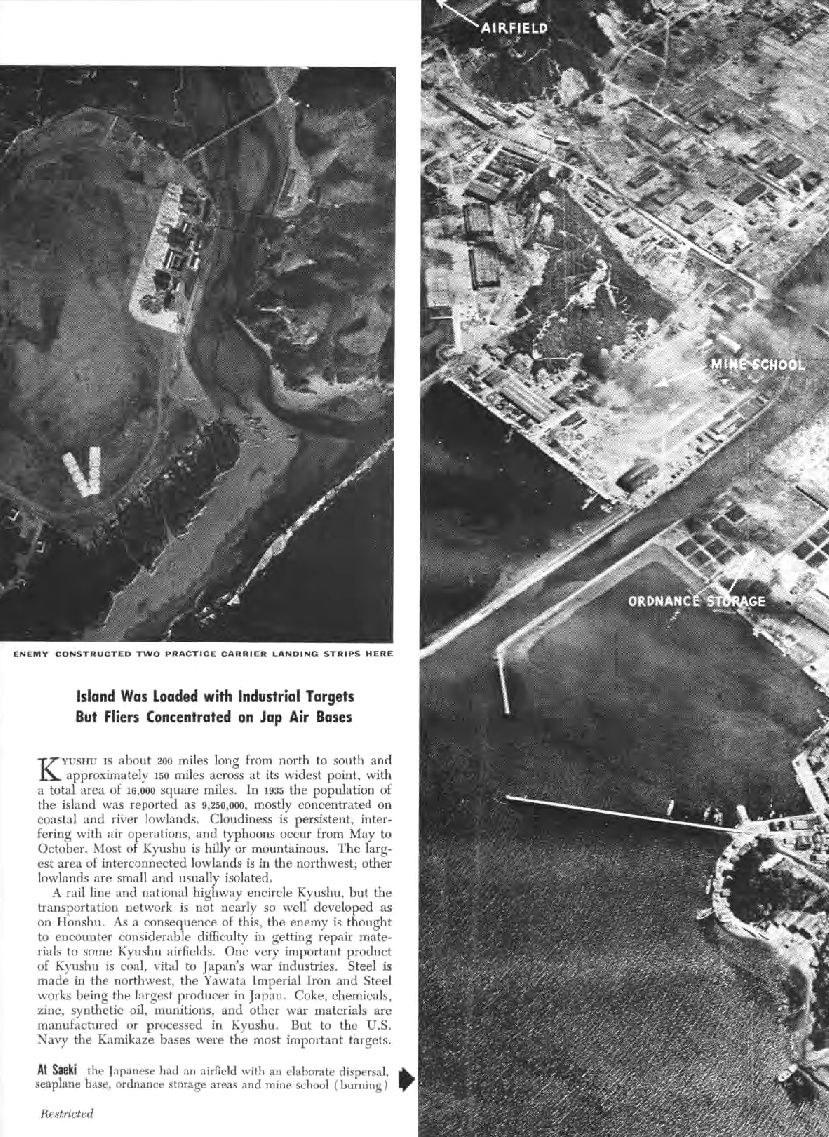

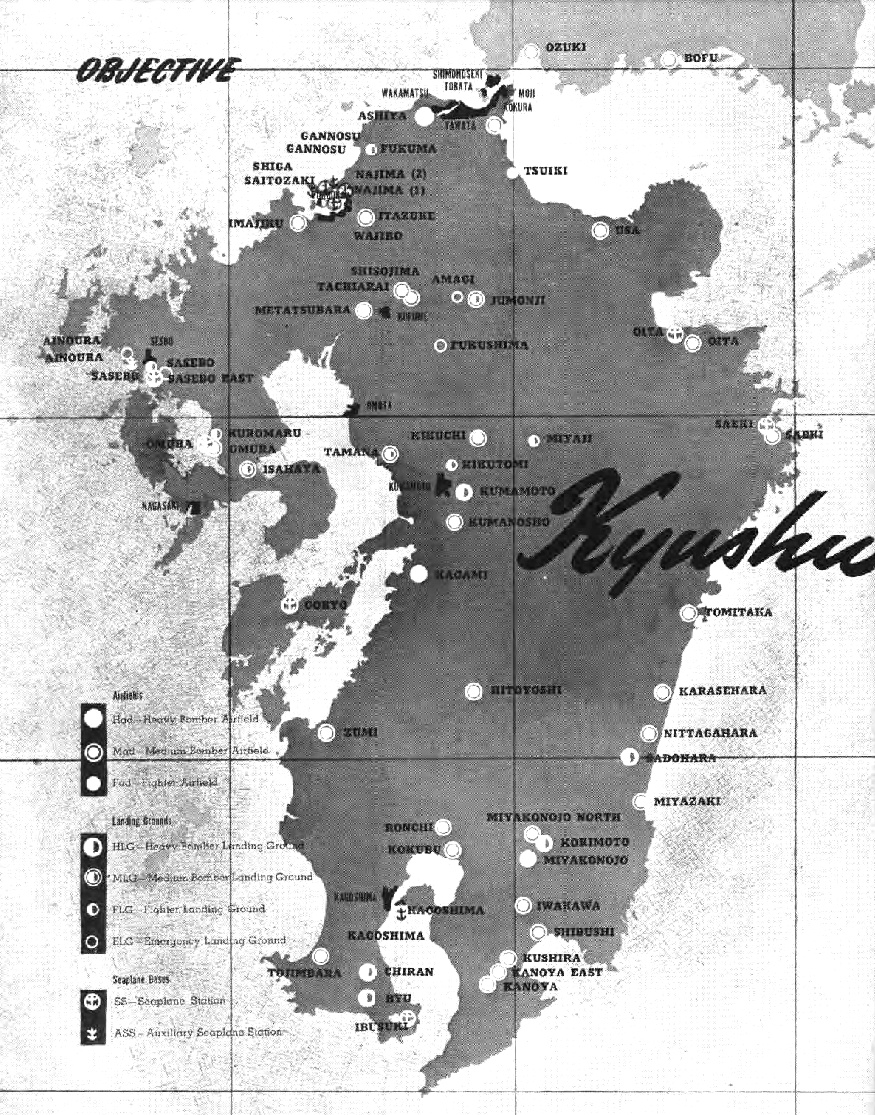

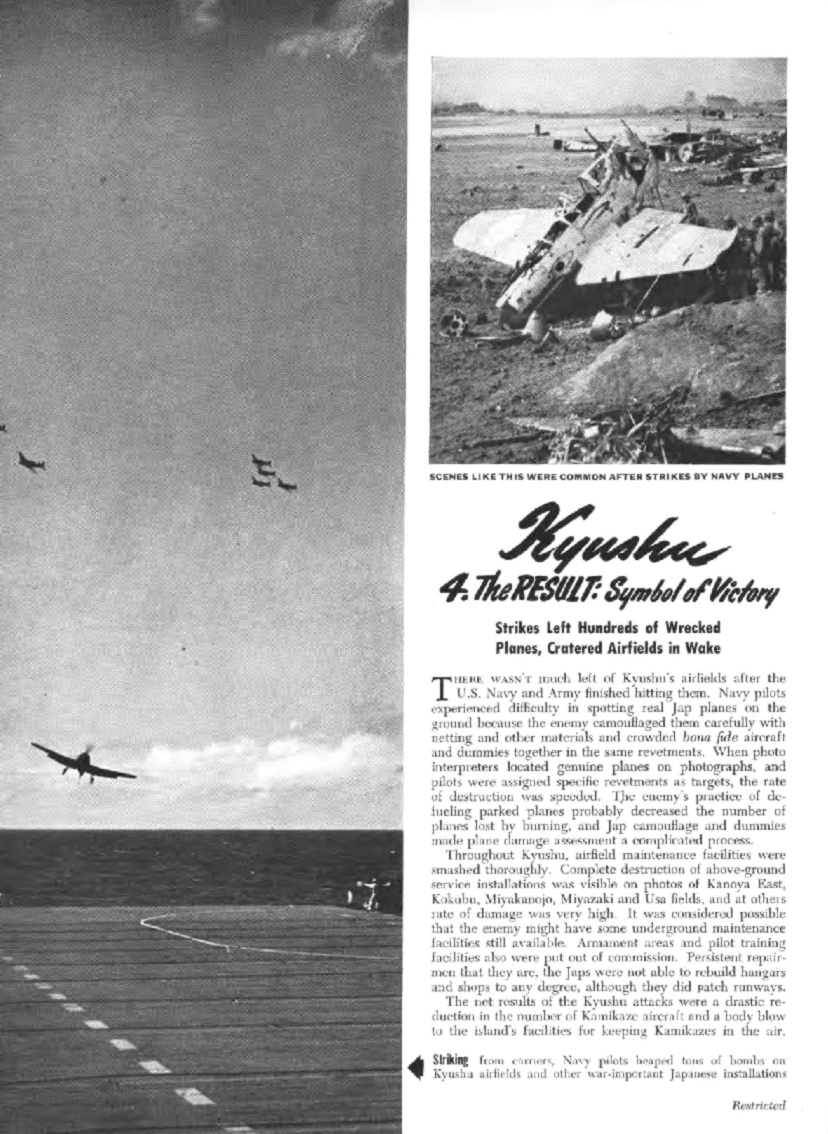

Tuttle wrote in December of 1945 about the Navy being anxious to be relieved of invasion support to go attack enemy ports and airfields – the source of trouble for the Navy in the form of suicide boats and kamikaze planes. The same scene had played out around Okinawa just a few months before. Once Okinawa was secured and had large fighter and bomber bases operating, the U.S. Navy unleashed everything it had on Japanese installations on Kyushu. The job was bragged about in the internal Navy magazine, Naval Aviation News. Here we share that article with you, copied right out of the August 15, 1945 issue.

Archives

All posts for the month January, 2015

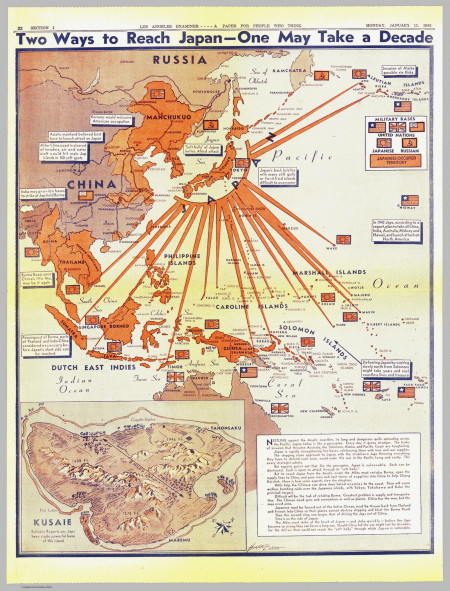

There is a newspaper “infographic” mentioned in the introduction to X-Day:Japan, from an early 1943 newspaper. The graphic is a map of the expansive Japanese empire, drawn to support an editorial position that the U.S. and allies should attack Japan by invading through mainland Asia. The paper, the Los Angeles Examiner, was sure that a campaign of Pacific island hopping would be a brutal and very long fight. “Two Ways to Reach Japan – One May Take a Decade”, the paper illustrates. You may notice that much detail is given of Japanese fortifications, but precious little of their proposed alternative.

It’s a nice map though.

[click for full size]

December 7, 1945 : X+22

Infantry in the field have little use for calendars. The day of the week means nothing to a man who is on the job all seven days no matter what, and hasn’t seen Sunday church services in months. Prayers out here are whispered on the schedule of artillery barrages and frontal assaults, not according to the program in a hymnal. The day of the month is immaterial to a soldier who pays no rent, though it should be cheap for accommodations consisting of a muddy hole and half a tent.

Those few here who do still keep track of what day it is recognize this as Pearl Harbor day. December 7th, four long years ago, the mighty Japanese Imperial Navy launched the surprise attack that ultimately brought us here. It would seem fitting for us to present them with an unpleasant surprise today, a little ‘thanks for the memories’ token of appreciation.

But I don’t think there will be any surprises offered in this part of the world. We assaulted this island with a quarter million combat troops and thousands of trucks and hundreds of tanks over three weeks ago. Our navy guns and artillery have pulverized in detail thousands of acres of Japanese home territory. I think they know we’re here.

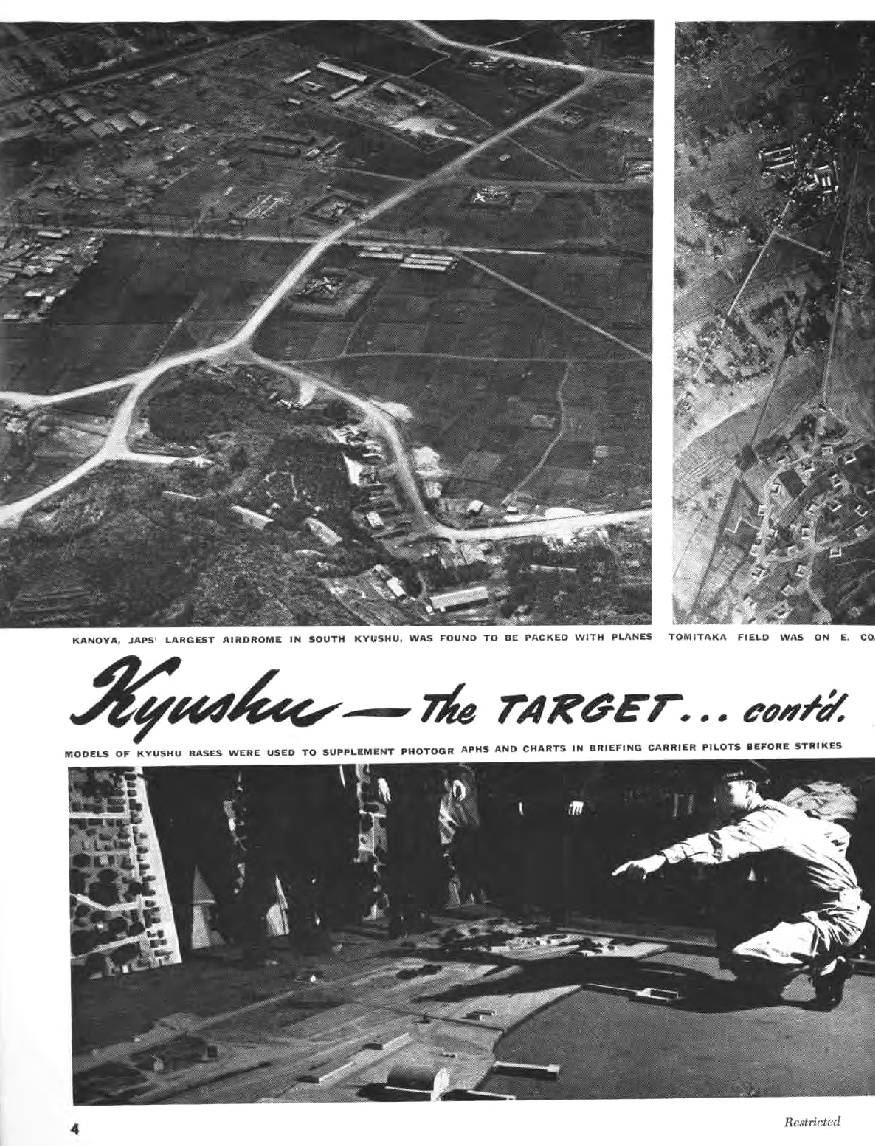

One surprise for them might have been that the air force is operating out of the large airfields in Kanoya, but they tell me that won’t happen until tomorrow. We have been flying ground attack fighters from small improvised strips near the beaches since early on. Engineers get busy on the larger permanent airfields as soon as they are taken, but regular air operations don’t commence until the field is out of enemy artillery range and threat of night infiltration attacks.

Kanoya has the biggest prize airfield in this area, but it lies in a valley between what a civilian might call ‘beautiful mountain backdrops’, or the military calls ‘commanding heights’. Those heights must be cleared of unfriendly ‘sightseers’ before the field is safe to use.

The 1st cavalry division has nearly flushed out the last resistance in the rugged peninsula to the south. The 40th division believes it has a firm hold on the near sides of the dominating Onogara-dake, a 3600 foot jagged mountain that I imagine will be featured on postcards they will sell at Kanoya if it ever becomes a civilian airport.

So the plan is by this time tomorrow to have aircraft of many types able to land at Kanoya, quickly turn around, and rejoin the fight. Each captured or improvised airfield that opens up in a combat zone gets put to use like this as soon as it’s safe, and often before that. I can tell you several reason why, and why it’s important.

The first and most obvious thing is that the hours flying back and forth from a far-back air base to the front don’t have to happen. An attack plane can make many short trips in a day instead of one long one, delivering its presents to a greater number of naughty boys on the ground. A patrol fighter can spend many hours circling a patch of sky, or fight until its guns are empty instead of the gas tanks.

Sometimes people look at a map which says that target such-and-such is now in range of aircraft type so-and-so and they think ‘Great, that’s a done deal! It’s practically ours already.’ But if they stop and do the math they’ll realize the severe limits of operating at range. If a plane has say 12 hours endurance, as they call it, and it’s five hours away from the target each way (assume it’s the same both ways for simplicity), the plane can spend no more than two hours “on station” over the combat area. If you need to have constant coverage, and let me tell you the boys on the ground would really appreciate it if you made that happen, it now takes a squadron of twelve planes just to keep two at a time where they can do any good. Flying at great distance is what they call a “force divider”.

A subtler point is the drain long flights have on the airmen. It’s physically taxing, and a unique mental strain. I’ve seen this in every flying unit, but the problem was most acute with the long range B-29 pilots I visited in the Marianas. A squadron leader in one wing, Major Ralph Praeger of Great Bend, Kansas, explained it to me. “A bombing mission from here might be 8 hours out and 7 coming back. All of that is over wide open deep blue ocean. There’s very little to do but think about the risks, how on every large mission a few planes don’t come back, and for no known reason. They just don’t show up. Getting shot at over the target area is one thing. It almost seems fair [the Japs shooting back], I think some guys look at it that way any how. The rest of it though, it’s just nerve wracking.” Indeed it isn’t fair, one little (relatively) aluminum skinned bomber up against a humongous piece of fickle nature like the whole Pacific ocean.

The B-29, being a complexity-no-object state-of-the-art machine, requires plenty of maintenance after a long flight. If you ever get a chance to see a cutaway of one of those 18 cylinder supercharged radial engines that power these bombers, four at a time, I recommend it. It’s a thing of beauty, but remember that all those parts have to keep working together dozens of hours at a time, without service or inspection, for a loaded bomber to do a job. Now, if you get a chance to see a cutaway of a bomber pilot, I do not recommend it, because it’s pretty messy, but also a lot more complicated than even that radial engine or an entire bomber. Bomber crews sleep for a whole day after a big job. After an all-day mission they typically aren’t asked to fly again for three days or more.

Another reason we want close land air bases sooner-than-possible is the way it opens up the Navy’s aircraft carriers for their best uses. Navy and Marine flyers love supporting ground troops, but they also love their ships. The majority of the sea based planes here have been doing air defense, and as we’ve seen the fleet itself is the thing most in need of protection. The British sent every carrier they could muster, but their planes are 100% tasked with protecting their own part of the fleet.

The impatient airmen I talked to today, watching their new home air base being roughly finished, explained that the carriers would be free to move around more once the Army lets them go, and one thing they’ll like to do is go hunting for small airfields and harbors the enemy suicide planes and boats have been coming from. Shooting Japanese planes on the ground and boats at anchor would bring us back to symmetry with December 7, 1941.

It’s been a grand show , but I will not be sad to see the navy pull up its circus tent and take the show on the road, with a different script.

[this is a portion of Tuttle’s entry for October 29, 1945]

A card game broke out that night in one of the enlisted barracks. That happened most nights anyway, but this one had very little to do with gambling. I was sitting in, mostly minding my ante, not wanting to take anyone’s money but not wanting this bit of material to be too expensive. (Editors are not fond of reimbursing wagers!)

The guys needed to pass the time thinking about something other than the impending unknown. We still didn’t even know when we were going, nobody did. We had a good guess where, though, and talked about everything but that. Still, people will drift back to what they have in common, and this group from all over a dozen states had only two things in common – the United States Marine Corps and whatever adventure it ordered them on next.

Finally a readily agitated private from Detroit, Dante Iacoboni, spoke up. “They say the Japs spent eight or ten months, twelve tops, digging in around here {Okinawa}. It cost us three months and a giant ass-kicking to kick them out of this [expletive]. How long you think they’ve had to dig in on Japan proper?”

After a pause another veteran Detroiter, Sgt. Ora Inman, answered him quietly. “About a thousand years.” The senior man on the deck, Sgt. Barnard, wasn’t even playing, as he fastidiously tended his gear, like he did every evening. But he was listening and spoke up right away.

“Listen up fellahs. I’m not supposed to say anything, but the word is that there’s a ‘surprise’ inspection tomorrow morning. Don’t tell ‘em I said so, but you might want to call it a night here and square away your gear now.”

The players agreed readily that they’d had enough cards anyway. They had a quick round of the usual arguing about who had cheated using the markings on the well worn deck and went to their respective barracks and tents.

There was no inspection the next morning.