[Tuttle took this day to catch the reader up on action around Kyushu.]

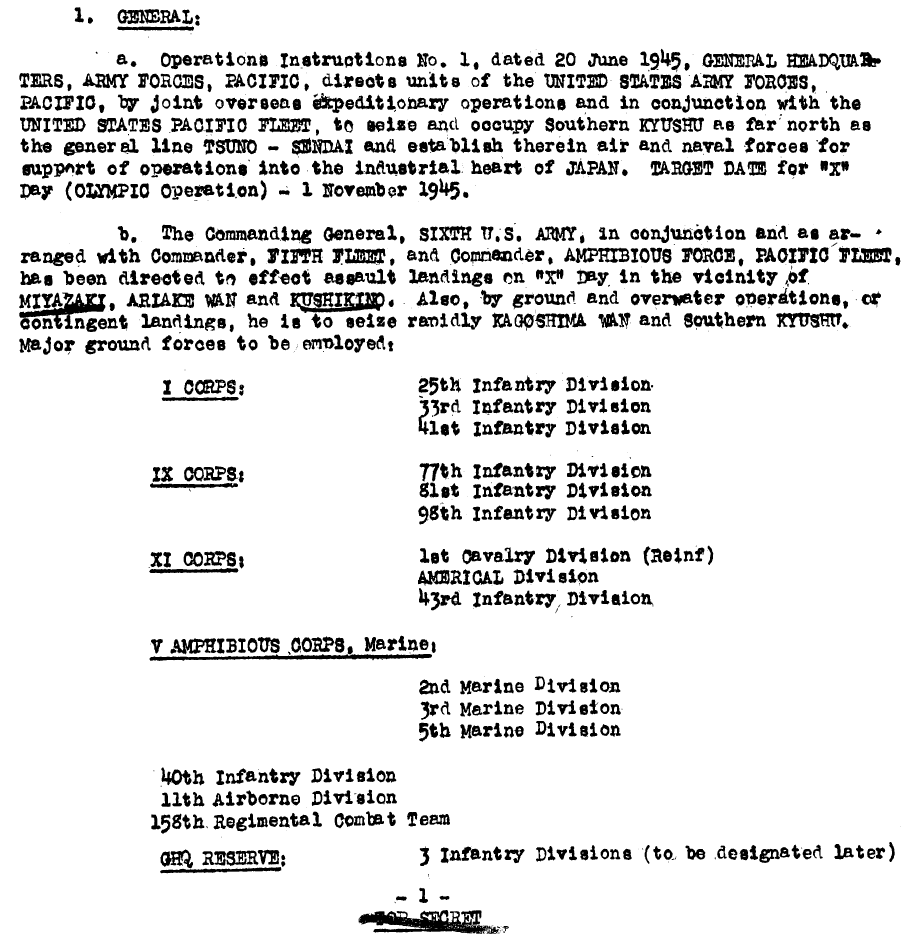

The 43rd Division is being pulled out, entirely. Its losses of officers and equipment can’t be replenished fast enough to make it worth feeding its idle units until that time comes. Its healthy men will be redistributed to other units, which are thirsty for veteran replacements.

The 1st Cavalry is the one division here to have four regiments, most others switching to three before the war. This may have been a compensation to the division for losing its horses in favor of trucks and scout vehicles. But that compensation is over. The 7th Cavalry Regiment is being split up, too expensive to rebuild while other units are too depleted to function. If it remains an active regiment, it will materialize somewhere back in the States as the regimental colors are presented to a column of new boot camp graduates.

The 40th Division is still being landed, charged with defending the whole middle of the line while everyone else prepares to move back into the mountains around Ariake Bay.

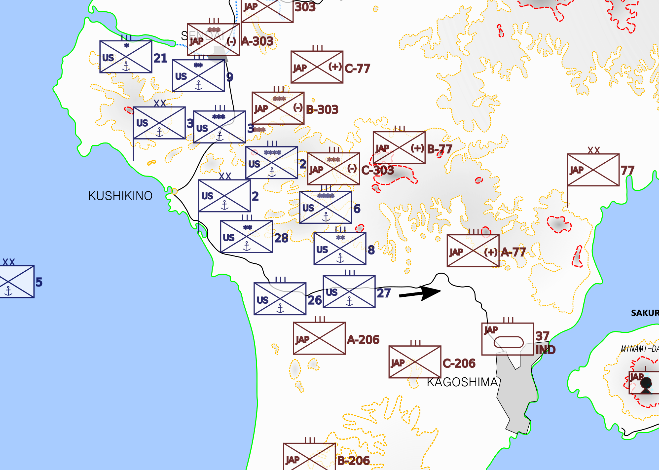

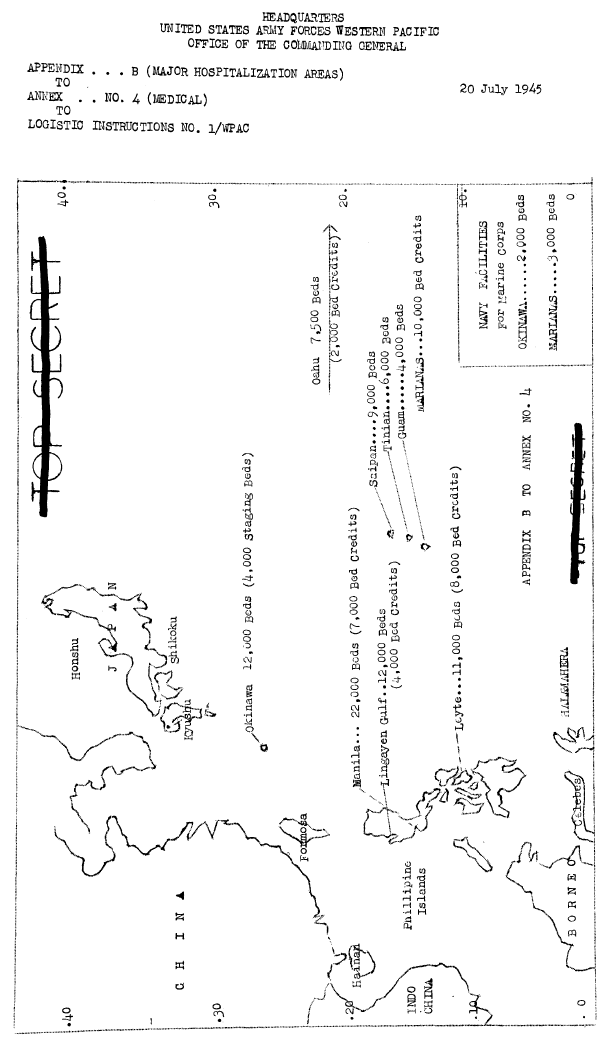

In the west, the Marines did take Kagoshima and Sendai, experiencing tough urban fighting, and attacks by civilians, after a week of slogging through a maze of defended hills. They scarcely hold either city though, as every night and some days heavy artillery from vantage points looking down into the cities hit known key points in each. The 2nd and 3rd Marine divisions hold the Sendai-Kagoshima line, having took in multiple waves of reinforcements to keep the advance going, ten miles in ten days.

South of Kagoshima the 5th Marine Division has been making painful progress down the five mile wide peninsula. It is a ¾ scale model of southern Okinawa, but there is only one Marine division instead of two Marine and two Army divisions working to clear pits and caves and tunnels which defend each other. All of it is in range of Navy guns, and I don’t doubt that it’s quite a show when they light up a stubborn hill. Engineers got to work in earnest on an airfield behind the Marines yesterday, sure that it’s now out of Jap artillery range. It should boost by half the volume of ground support flights they can run on a good day.

South of the Marines, the 77th and 81st infantry divisions made good progress at first, pushing through open flat land west of Kaimon-dake, which was undefended. The small mountain was expected to be a tough fort and the Navy was almost disappointed at not getting to blast at it. The Army divisions are now coming into hilly territory and finding the going considerably slower and more bloody.

In the east around Miyazaki the story has been mixed. In from the beach is a plain almost ten miles deep. American spotters can observe all of it and direct Navy guns on any part quickly. The Japanese did not try to fortify it. Miyazaki itself was largely deserted, save for bands of scared or angry civilians who did not evacuate with the others. Some of them attacked American soldiers in small groups, to limited direct effect but it makes our soldiers ever more wary.

South of Miyazaki the 25th Division did the tough job of taking hills close to the beach, which overlook American camps. There the Japanese did defend, and it was all the 25th could do to take the first line of mountain ridges before digging in to rest. Miyazaki will become the first developed place we really hold on Kyushu. Its port and airfields will be opened up ‘soon.’

Early on the beach head at Miyazaki faced a dress rehearsal of the big counter attack that just finished in Ariake Bay. They figure that parts of “only” two veteran Japanese divisions drove into American lines, supported by about fifty tanks. The attack at Ariake was more than twice as large.

One thing that has everyone surprised is the number of Japanese tanks that have been thrown at us. Intelligence men are optimistic that we’ve already seen most of what they can muster, but when pressed they have to admit they just don’t know for sure. Movement of troops far to the north has been seen by our aircraft when weather permits. When weather does not permit observation, Japanese reinforcements can move without aiding our insight.