[After the Japanese attack into Ariake Bay, Tuttle rode along with a beat up infantry platoon as they pulled out.]

Moving the other way on the coast road in a steady stream were war-weary soldiers and trucks. One truck was barely half full of tired men. I knew it was full to capacity with stories to tell, so I hitched a ride.

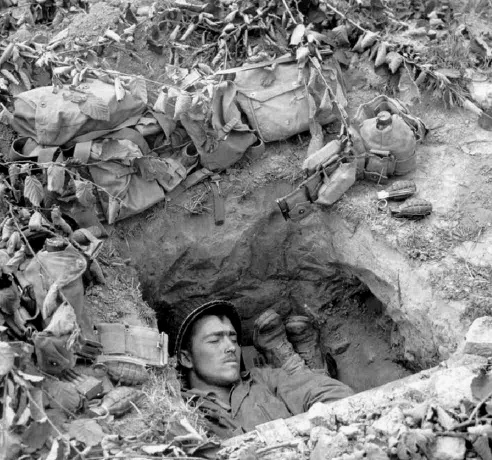

Benches along either side of the bed were occupied by men sitting upright or sideways or variations in between the too. At the front on the right side was the only officer. First Lieutenant (provisional) Manchester B. Watson had his feet up on the bench and was sound asleep, possibly dreaming of his hometown of Greenville, South Carolina. “He ain’t slept in five days,” Private Johnnie Garrett told me, along the way to mentioning that he and the Lieutenant were from the same town.

On the flatbed floor was a chaotic assortment of equipment, from cases of grenades to post hole diggers. I picked up an ammunition belt that had all of 13 cartridges left in it. Private Garrett explained, “They told us to grab whatever equipment we could and move out on the first truck that came for us, after we carried back injured and dead all morning. Everyone took up exactly one armful of junk, tossed it in, and got on board.” Some of the men were asleep sitting up.

Behind us was towed a small artillery piece, an Army 105 mm, I think. I asked around and learned everyone on the truck was with the same infantry platoon. “That’s not ours, and we couldn’t tell ya where its crew got off to. Nothing but empty crates around it when we found it.” Corporal Judson McBrine of Newport, Rhode Island continued, “The driver couldn’t stand to leave it there. Whoever left it took the breech pin with them , but otherwise it’s in good shape.”

For the rest of the trip across Ariake Bay I heard competing stories of ocean fishing from men of the unit. Most of the 43rd Infantry Division was from New England, and anyone who wasn’t a commercial fisherman was a keen angler, or at least talked a good game. There were nineteen men on the truck. I asked about the rest of Lieutenant Watson’s platoon.

“This is it, the whole thing.” The new voice was Staff Sergeant Clifford Blais, who’s accent from Providence they tell me is different from the Newport man. I can’t tell the difference. “They sent two trucks to bring us back, and said a third was coming. We sent the second away and the third one is probably still looking for someone to carry.”

I moved up front with the Sergeant, the ranking non-com on board. We talked quietly as he filled me in on the experience of his unit so far. They were among the first ashore and had been fighting in the hills north of Ariake Bay since the first day.

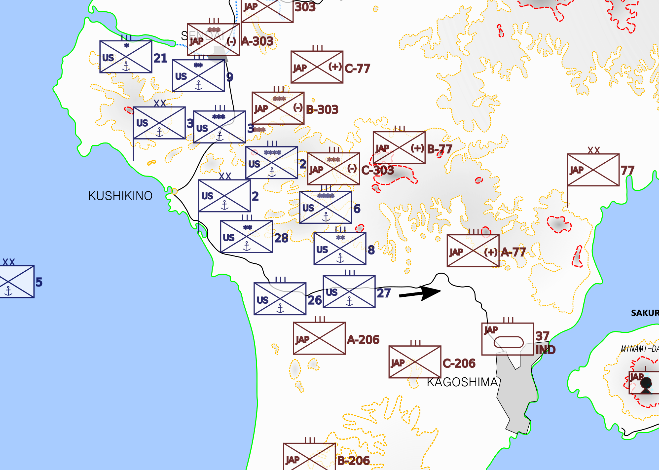

Their regiment, the 103rd, had no trouble getting to the beach. Other parts of the 43rd Division had to maneuver around shipwrecks in the shallows and took sporadic but accurate heavy fire from hideaways in the hills. The 103rd Regiment rushed on toward its second day objectives right away – up into those hills.

All of this was perfectly predictable to the defenders, so the American charge went right into a trap with multiple rows of teeth. Little American artillery had made it ashore yet, naval support was limited by the angle of the hill slopes to the bay, and air support was limited when anti-aircraft guns became priority targets for the Navy attack planes. The infantry had to knock out positions one at a time with rifles, grenades, and a few bazookas.

Obscured by smoke from bombardment and brush which had survived the bombardment, Japanese positions did not reveal themselves until American troops were at close range. Each one generated casualties that had to be carried back to the beach, as a plan was improvised to regroup and take out the new enemy pit or pillbox or cave.

They kept at it for five days, repeatedly taking out small networks of enemy positions and seizing small objectives, until the last hills with direct view of the American beach were under American boots. A halt was called there, not that it mattered. Sergeant Blais said they were spent. They couldn’t take another ant hill, let alone the ever larger mountain peaks in front of them. Word went up and down the line that every other unit was in about the same shape.

In the course of fighting off the large Japanese counter attack of the previous days, they fell back twice, taking many casualties back with them. Fighting was hand-to hand during one early morning charge. Some small units elsewhere in the division were wiped out to a man on the worst day. But other Army units closed up those gaps, recovered the dead, and retreated in some semblance of order. This was a veteran division, and had been for some time.