[Tuttle was keen to include textbook details of tactics from the better small infantry units he saw.]

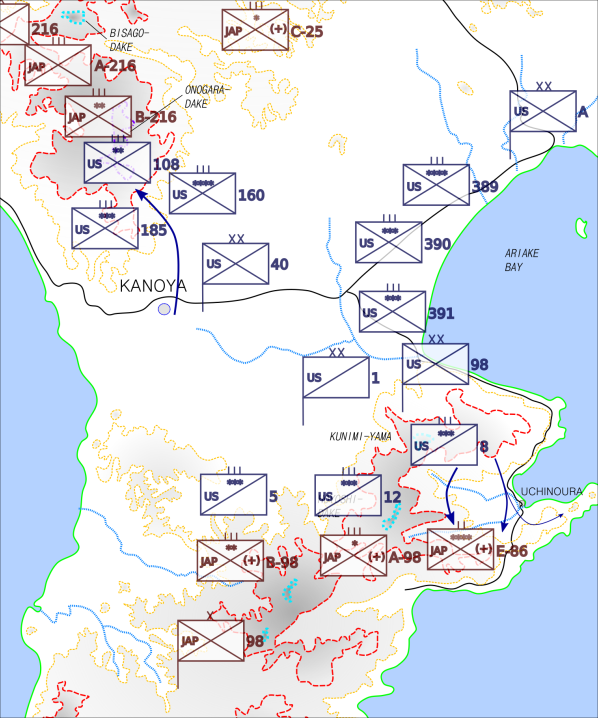

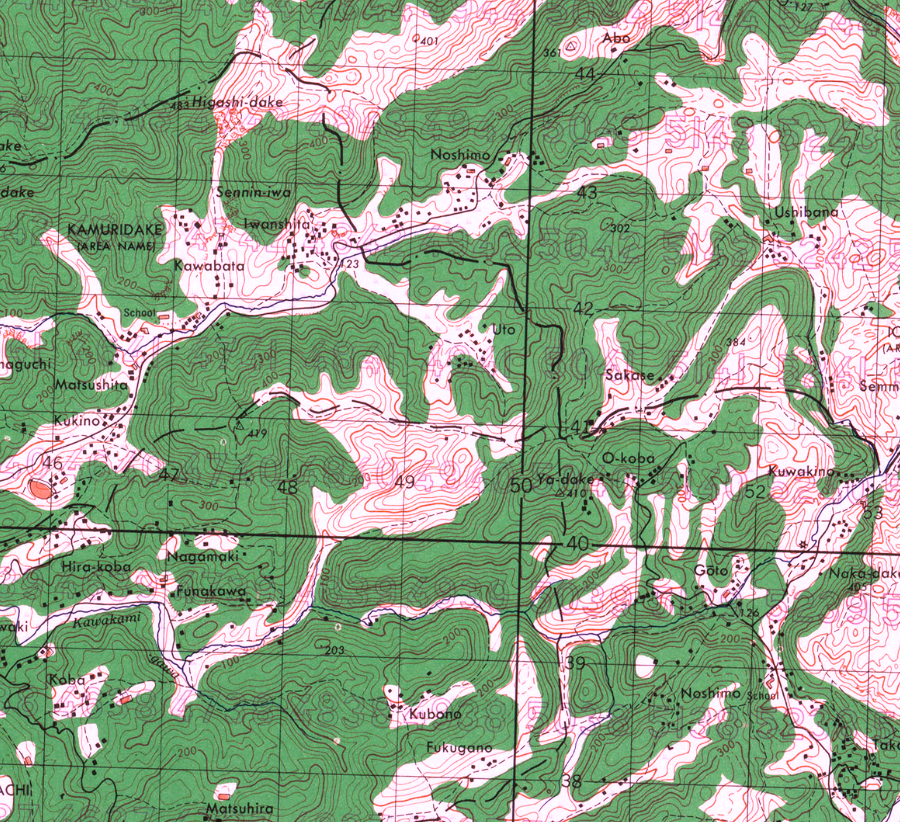

Charlie Company, 3rd Battalion, 188th Glider Infantry Regiment, 11th Airborne Division, welcomed me in to their un-named hilltop HQ. The artillery behind them had rated hill “number 260.” This unit would not have a named home until they took a taller hill across the valley, hill “number 367.”

Company CO Captain Arthur Leonard told me a bit about the trip forward. “We practically hiked straight in. We took up old positions the 162nd [Infantry Regiment] held and then another couple hills past that.” He pointed back up to the mortar squad behind them that I passed on the way. “The Japs had pulled out. All we saw were two snipers, and we’re still looking for booby traps here.” He drew a wide circle around the camp which had been a Japanese infantry camp facing the other direction. Captain Leonard said the land here isn’t too different from where he used to hunt in the Alleghenys east of Pittsburgh.

Platoon Sergeant Walter Strauss, also of Pennsylvania but more accustomed to the flat Erie lake shore, was standing next to us and pointed out the sandbag berms his men were set behind. “We even got to reuse the Jap sand bags. Except they left grenades jammed under some of them.” That drew a couple chuckles from some shovel-hefting enlisted men, even though the first grenade caused two casualties. “I’ve sent back three medical cases so far,” the captain explained. “One of them was a bit of grenade shrapnel in a guy’s butt, but another was a twisted ankle his buddy got diving from the grenade. He tumbled straight down the steep end of the hill, arms swinging like he was swatting off bees.”

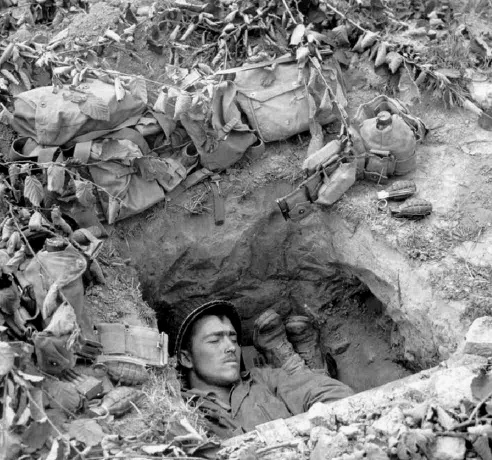

The unit was digging in for the night. Some gentle encouragement from the sergeants was required to get the holes textbook deep, as they had yet seen no enemy soldiers nor any artillery rounds. I had drawn a bedroll and extra blanket to camp under as winter weather was finally being felt on the temperate island. With clear skies the temperature would get below 50 and stay there until the sun made its brief appearance the next short day.

Artillery was heard that night, to either side of us, less than two miles away. They were short barrages, but of heavy caliber from far away. We never heard the sound of the launch, which would have followed some seconds after the report of the exploding shells in the passes east and west of us. Some small villages sat in the river valleys that made up each pass, but all were deserted save for a few American sentries.

Before dawn the third watch roused everyone and men fumbled to gather their gear under a moonless sky. At the pre-appointed time, artillery and mortars from several distances behind us began their almost daily ritual. Flashes of light walked up the hillside opposite us, and on many other faces up and down the American line. When we couldn’t see the flashes any more, the explosions were on the back sides of the objective hills, and it was time to move out.

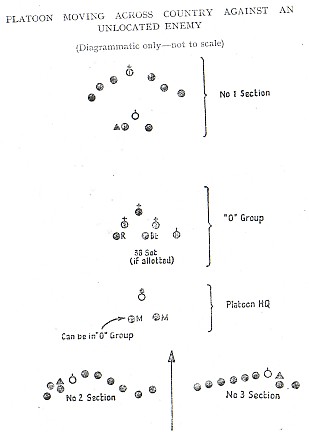

The company advanced in two waves of squad columns, in a chevron formation. At least that’s what the captain told me it was. I went out behind the second wave in any case. The next peak was about three-quarters of a mile away, but we had to go down about two hundred feet and up three hundred to get to it. Our side was a single slope, but the opposite side was broken and wavy.

We had some light by then. Groups of men moved in and out of the remaining clusters of trees. Previous artillery fire had roughly cleared deliberate sight lines, which were good for us to spot the moving enemy, but of course they work both ways. Half charred felled trees were a nuisance everywhere.

A half hour passed before the first shots were fired. A few rifle shots went up into trees that could hide a lurking sniper, but a submachine gun was preferred to rake the tree tops. Forty minutes of careful hiking, two or three stumbling steps down, followed by a rifle-ready scan of the opposing hill, had the front wave at the bottom of our hill. Runners reported adjacent companies all on track and no trouble to the sides. The lead squads advanced again, up the next hill.

Columns drifted apart some in the twisted terrain, and lieutenants made adjustments to keep us lined up and to cover blind spots. The point of the advance was moving directly toward the crest of “hill 367,” groups of men trailing it left and right in a vee. They paused at the last trees before a clearing at the top, letting the line come up more even. Then the whole line moved forward over the top.