[Still on a command ship, Tuttle watched action toward the shore through his trusty field glasses.]

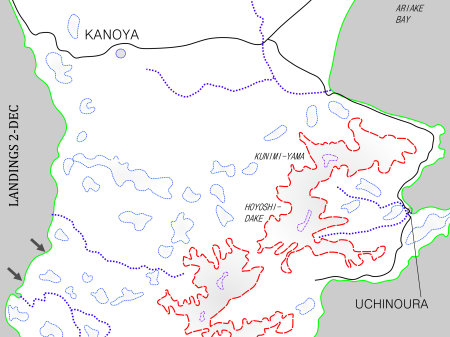

Early in the day the 5th Marine Division sent one battalion south as a reserve for the Tanega-shima fight, and now it has lost another permanently. Staff officers are generating stacks of paper to reassign veterans to head up replacement companies. Over a thousand raw Marines, fresh from basic training, will be absorbed into the division, and it will have no opportunity to train them before it gets ashore.

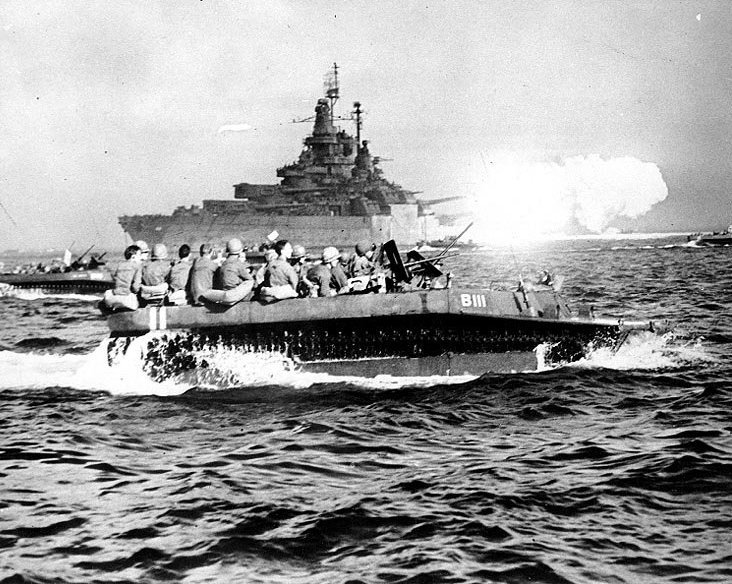

Once the orders come down, our small boats will be very busy moving men around between transports. So I took the opportunity to get a ride in to the beach while I could. Late in the afternoon I climbed over into a Higgins boat, under the occasional shadow of a heavy shell streaking in to a requested coordinate. Fighting on the beach was mostly out of sight by then, but the sounds of modern war echoed out to fill the air over the entire fleet.

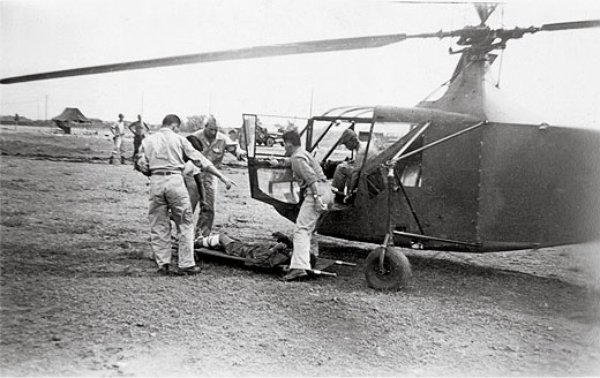

An ethereal calm settled over the battle as a novel apparition materialized. First a rhythmic slow strum, like off a cracked old out-of-tune cello, began to fill the quiet instants between rifle cracks and mortar tube ‘whoomps.’ Then the battle stopped altogether as the first helicopter anyone there had ever seen came into view.

The curious non-flapping bird moved quickly across the water, seeming dangerously low over the trundling transport boats, but probably well above them. Our own heavy guns had stopped firing to clear its passage into the center of our beach head. The helicopter slowed as it approached the shore line, lowering to a hover just above a deliberate clearing amongst all the debris of war, about 100 yards from the water.

It dropped to the ground and its body came to a rest, rotor still spinning almost too fast to make out the blades. Medics moved confidently under the blades, as if they’d practiced the maneuver (I assumed they had). Some critically wounded Marine was loaded in behind the solo pilot. The noise of the rotors picked up its rhythm before the medics were even clear, and the nature-defying aircraft was up again, moving the precious cargo to a hospital ship out in the fleet.

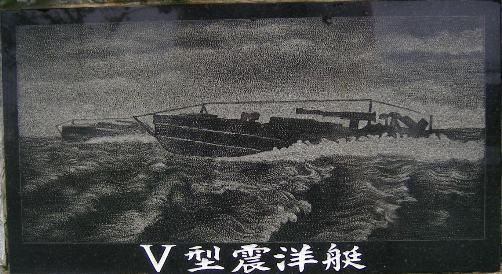

Another helicopter was already heading in to the beach. The hole in the combat noise caused by the first whirlybird began to close. Small caliber guns opened up on targets of opportunity, such as an individual Japanese soldier or American Marine who had stuck his head up to catch the side show. Larger Japanese guns, including some that had been hidden and discretely silent, began to bark as the second helicopter came close to landing.

Our medics worked fast to load the next injured man, and Marines shot back to silence the new entrants into the battle, but the Japanese guns were pre-sighted and quickly found their mark. The second helicopter was ten feet off the ground when it exploded into a shower of hot metal scraps and one screaming dying engine.