It must be emphasized that X-Day: Japan is not an academic work. Still, we’re proud of the research and detail that went into it. Some readers have asked for more information about certain details, or for a longer list of references than in the bibliography.

In the margins of the main manuscript can be found links to many of the little facts that decorate the novel. We’ve compiled them into a list, sorted by the Tuttle journal dates in which each was found. A bunch of them are given below. The list will be completed in later installments.

July 16, 1945

FM 30-26 Regulations for Correspondents Accompanying U.S Army Forces in the Field,

– archive.org

July 19, 1945

Macarthur’s personal plane, and his assistants,

– donmooreswartales.com

– ozatwar.com

Flying across the Pacific in a hurry,

– wikipedia.org

– wikipedia.org

– uswarplanes.net

July 22, 1945

USO,

– archive.org

Hawaii – it’s history, economy, defenses, and outlook – as of late 1940,

– fortune.com

Prostitution in Hawaii,

– library.manoa.hawaii.edu

Actual USO show,

– gvnews.com

– abebooks.com

July 23, 1945

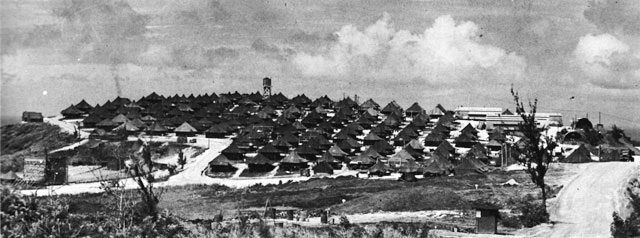

Training on Hawaii up in Camp Tarawa,

– Chuck Tatum, Red Blood, Black Sand

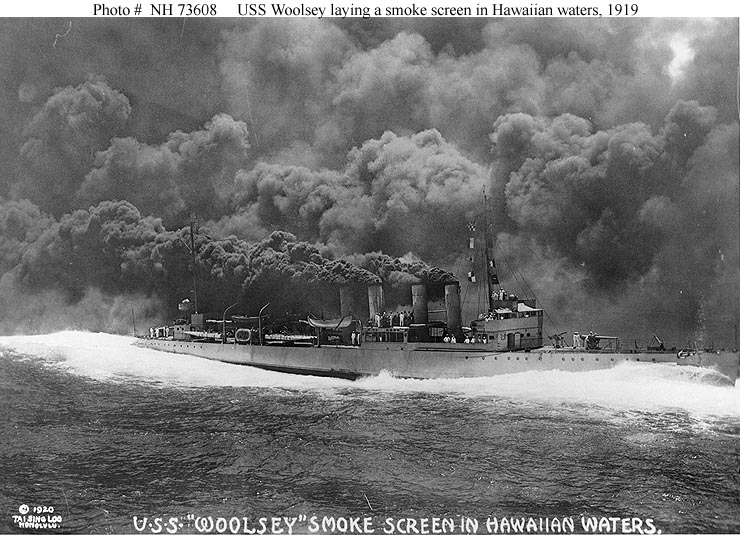

DE’s by class and commissioning year,

– ibiblio.org/hyperwar/

July 26, 1945

NATS,

– wikipedia.org

– vpnavy.org

FDR’s line crossing ceremony,

– ww2db.com

July 27, 1945

Marpi Airfield, Saipan,

– airfields-freeman.com

July 28, 1945

SB2C Helldiver,

– wikipedia.org

Marine close air support,

– ibiblio.org

July 29, 1945

Facilities and engineers in the Marianas,

– ibiblio.org

Floating dry-dock example,

– navsource.org

– navsource.org

Log of bombing missions from one group,

– 39th.org

July 30, 1945

458th Squadron, 33th Bomb Group,

– rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ny330bg/

mission log including radio report from Ray Clark,

– rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ny330bg/

August 3, 1945

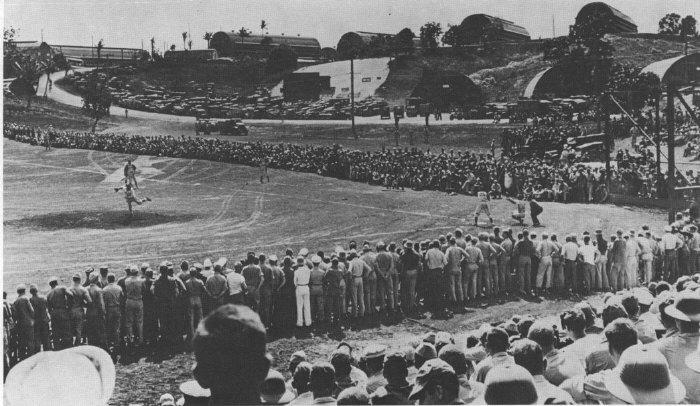

Baseball in wartime,

– baseballinwartime.com

Navy reports on typhoon of June 1945 (Connie),

– history.navy.mil

USS Red Oak Victory, cargo ship AK-235 [MUSEUM SHIP],

– navsource.org

– navy.memorieshop.com

– richmondmuseum.org

Shortage of loading berths at Okinawa,

– Nimitz Gray Books [multiple references]

August 6, 1945

Yonabaru Naval Air Station,

– rememberingokinawa.com

Buckner Bay and Navy HQ buildings,

– rememberingokinawa.com

Sinking of the USS Indianapolis,

– history.com

August 9, 1945

Trial of Captain McVay of the Indianapolis,

– ussindianapolis.org

August 10, 1945

Active airfields on Okinawa, 1945,

– wikimedia.org

August 16, 1945

USO show on Okinawa,

– rememberingokinawa.com

Betty Hutton,

– bettyhuttonestate.com