[Preferring to be up front near the action, Tuttle often found himself in sight and smell of it.]

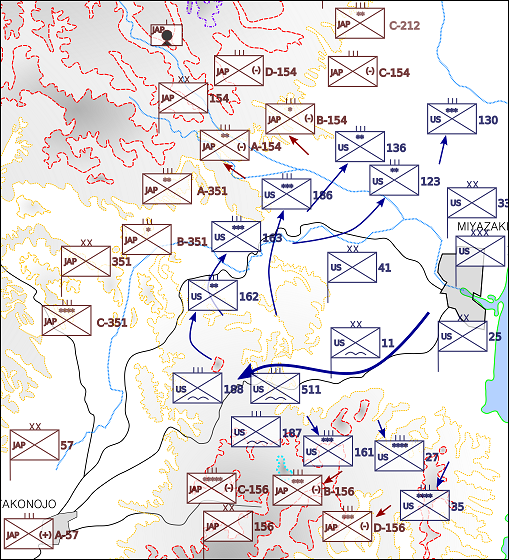

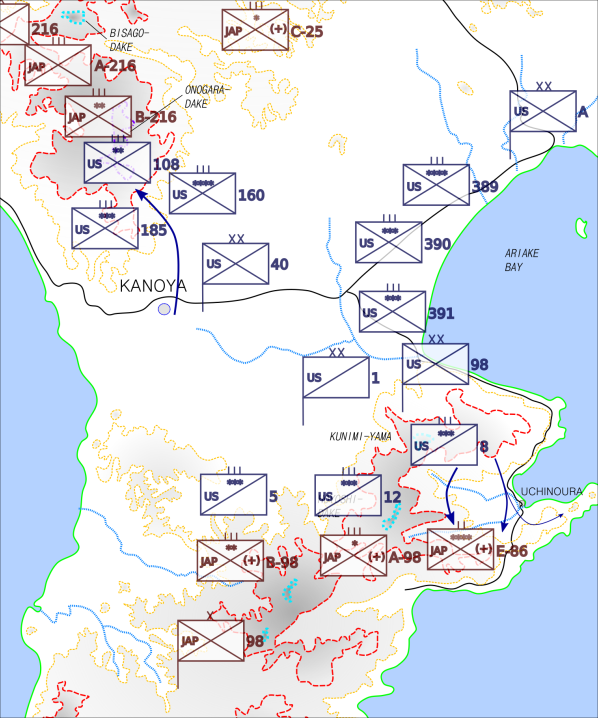

The last bit of the day’s objective terrain was a jumbled mat of misshapen hills and winding shallow ravines, southwest of where we broke camp that morning. Contour lines on the map of this patch almost draw out rounded letter shapes. One squad ran out of high ground to scout over and moved down into a curving ravine for a while. They rounded a turn, and patient Japanese gunners waited until all dozen men were through before opening up. They were about 300 yards away and downhill from where I stood on a high clearing, the company command post for that hour.

The squad was immediately pinned down and cut off. No one could see them down low and around a bend, not even the adjacent squads. The sounds of at least two Japanese light machine guns and cries of “corpsman!” amply illustrated the situation. It was the middle squad of the middle platoon, whose lieutenant was trying to move the others to assist. But mortar fire, of mixed sizes, dropped in around the trapped men, keeping their help at bay.

Captain Leonard got involved, sending another platoon around to the left, staying low through the next couple ravines, to put eyes on the enemy machine guns. A radio man dialed up our own mortar section, ready to relay spotting to them. On the right, where we had no friendlies for some distance, the heavy weapons section set up machine guns to cover the gap while the company worked through its current problem.

Above us in the bright clear sky there were layers of fighters and attack planes circling, waiting for targets. The Captain cursed aloud, “We were supposed to have an air controller down here by now! God knows where they all are.”

The sounds below changed as another two Japanese machine guns started to fire. A squad of the other platoon was now pinned down like the first and soon bracketed by mortar fire as well. From somewhere to the west, small and medium artillery rounds began to pepper the whole area occupied by the company, heaviest around where the machine guns had set up.

It was a trap, a perfect ambush, and we were all the way in it. Holding still ensured being gradually consumed by artillery fire. Pulling out meant abandoning two dozen trapped soldiers. The captain stood up and yelled out, “Airborne! Give ‘em hell!!”

The radio man called in our situation as Captain Leonard ran forward to the platoon rears. This would be quick, but not a mad charge forward. He drew up a play like a sand lot quarterback, and his veteran unit snapped into action. I got down as close as the scattered remaining brush would still allow me a good view, which was about as close as I dared.

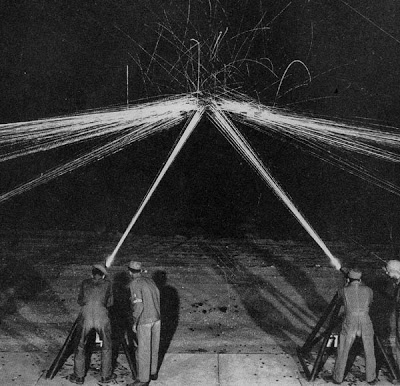

Two .30 caliber machine guns were marched along on the right, continuing to move so as to not be static targets for the mortar spotters. The gunners fired from the hip, each aided by two ammo handlers, sweeping the top of the high ground opposite where our men were pinned down. It was a long crescent shaped ridge, flat on top, bare in patches from many rounds of bombardment. The enemy machine guns could not be seen, but they had to be in that ugly rock. Our roving machine gunners were exposed, but they were suppressing any infantry that might be ready to protect the machine gun pits.

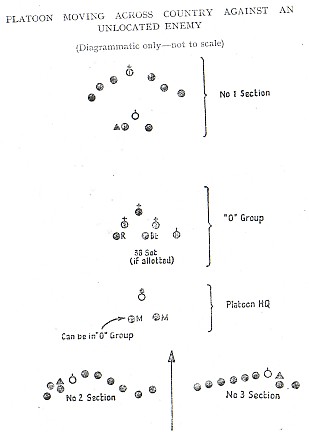

The surviving platoons, save one reserve squad, hustled forward, crouching low. Explosions kicked up dirt around and among everyone. They dodged between clusters of surviving brush and along hill sides, until they could see the problem.

The ravines our boys were stuck in curved together into a vee shape. The vee pointed directly into the arcing hill, across a small flat. Guns dug into the hill could fire down both lanes. A higher ridge some ways west afforded visibility to enemy spotters observing any approach into the trap, or anyone trying to flank it.

Captain Leonard crawled with the center most squad, on the high ground in the point of the vee. From there one could make out the Japanese machine gun positions, more by muzzle flash than physical features of the emplacements. Mortar and artillery rounds began to close up on the platoons as Japanese observers figured out where they were all clustered. The captain stood up and fired his .45 pistol at the enemy hill.

On that mark everyone rushed. One of our machine guns to the right began to rake the hill side, joined by three BARs. Two bazookas fired rockets from the left toward different Jap guns, both near misses. The Japanese gunners didn’t flinch at the direct fire. They had nowhere to hide or retreat. One immediately swung over to where the bazooka rockets had come from, tearing up one of the teams.

American smoke grenades began to fill the air in front of the machine guns. The Jap guns fired continuously, sweeping the whole flat, for a full two minutes. Certainly their guns would be melted quickly. Artillery fire from the distant ridge began to land near the crescent hill, undeterred by the presence of friendly forces. Aircraft began diving on the taller ridge, by direction or from seeing our plight themselves. The Japanese artillery men would have to close up shop and hide.