[The 8th Cavalry set up advance through rough terrain, Tuttle and Major Lawless sitting in with the only mechanized element of the operation.]

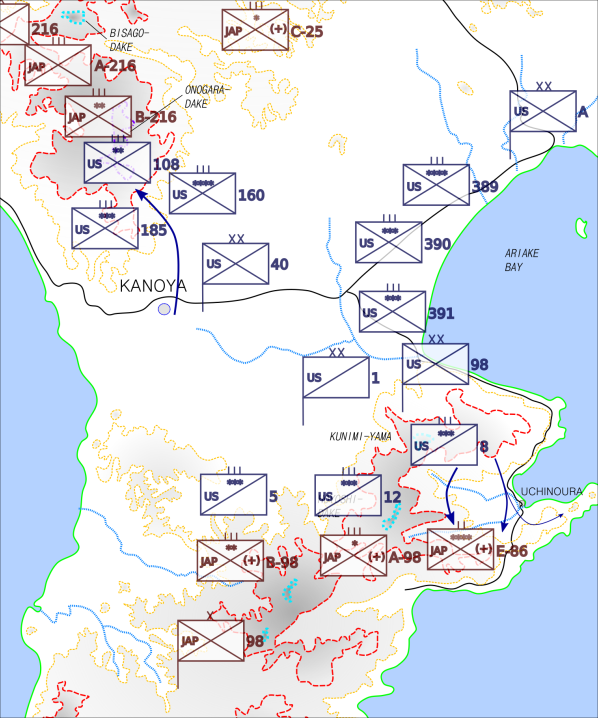

The central southern part of Kyushu is a mountainous peninsula which points acutely out into the East China Sea. It defines the east side of Kagoshima Bay and one shoulder of Ariake Bay. 18 miles wide at the first foothills, it tapers south by southeast 25 miles to a sharp cape which is the southernmost point of Kyushu. Except for a steep east-west pass about halfway through, the peninsula is a continuous sequence of named mountains, joined and divided by long ridges which run in a variety of directions. Small and large rivers cut through every valley. All of them ran high in the rainy season we met on Kyushu.

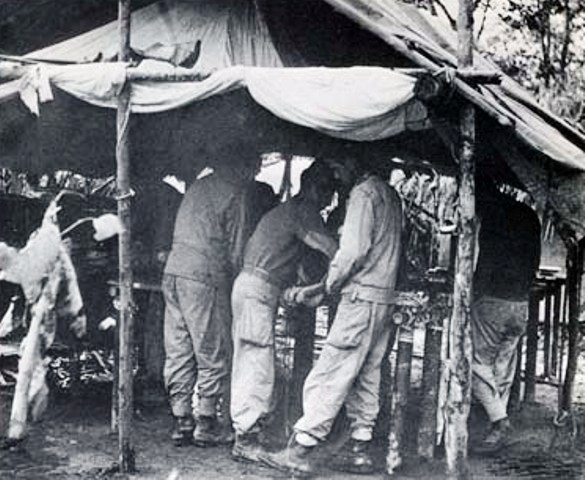

Yesterday afternoon I was taken by jeep up dirt trails which only a very stubborn driver can make usable by motor vehicles. The 8th Cavalry Regiment took most of the 2500 foot mountain Kunimi-yama and had been camped in spots on and around it preparing for their next move. This morning I went down the east side of the mountain on an even worse trail.

Like all the mountains in the area, it’s far more than one single hill. From each peak that gets the name, there are a cascade of smaller peaks, divided by uneven valleys. The land is practically impassable. Beyond a few logging roads, there is no organized access. So American soldiers have been practicing with ropes and climbing gear, and engineers are ready to tie up cable hoists right behind them.

Through this land, the 8th was to move forward, roughly southward, in a continuous line, gather up in the next long broken valley, and attack up the next set of slopes. The east end of that valley holds the small fishing city of Uchinoura, which sits in a small bay at the southern tip of Ariake Bay. I was to ride with an armored column that would take the coastal road around the mountain, ride into town, grab the one good river bridge there, and secure it so our infantry could be supported into the next ridge line.

Our side of the operation could expect good naval support from the small bay. Farther inland the infantry would rely on close air support. Clear skies afforded unrestricted air operations, for once.

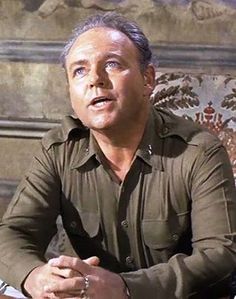

When I first arrived I was delighted to find the British reporter Major Peter Lawless, my tent mate on Okinawa, with us at the top of the mountain. We caught up on what each had seen during the ‘big show.’ He was a late comer, having only got a cast off his arm two weeks ago, after getting it broken pitching in to rebuild on Okinawa after the last storm. He went into the eastern beach head at Miyazaki on about the fourth day.

Major Lawless said he saw the 25th Division do the same thing we are about to do, on a smaller scale, a couple times. They have a long sequence of steep ridges to deal with down the coast. They could get naval support, like we were to have, but were exposed the whole time coming down the steep face of the ridge they held before even starting to work up the next ridge. It was difficult, and deadly when the Japanese chose to make it so.

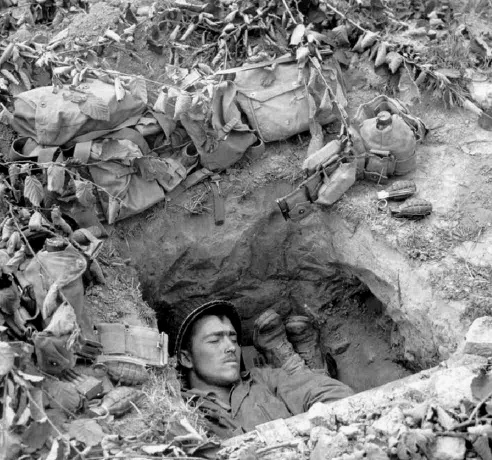

Among dense trees in a rare flat spot we shared a crowded tent with an assortment of young officers, catching whatever sleep we could before getting up before dawn to pack up. We would have only about ten hours of daylight to work in. As soon as there was just enough light to see ten feet, our jeep was off.

Major Lawless and I shared the jeep with its driver, Corporal Donald Bignall, and an interpreter, Captain Doyle Dugger. Captain Dugger picked up Japanese the hard way, in schools the Army rushed to set up at the start of the war. He said the foreign language options at a small Catholic college in southern Indiana didn’t venture much beyond Latin, Greek, and German. Corporal Bignall learned some Chinese swear words growing up in San Francisco, and is sure any Japs we meet would understand them just fine.

We all cursed together, in every language any of us knew, as our jeep was tossed down the old mountain trail, more by happenstance than by steering and throttle. Supposedly a scout of some sort had run through here before the operation was approved, but we had our doubts. The mountain was not our only problem, as there were other vehicles ahead of and behind us. We had to stop short on several occasions as the jeep in front got set up for a tricky turn, praying that the one following us got the message in time.

Finally we came out through a tiny deserted village onto the coastal road. The sun was uncomfortably bright over the ocean, as we emerged from two hours of navigating through an evergreen forest. We moved back along the road to find a place in the attack column that had formed ahead of us. Driving in the dark all night, a few tanks and at least forty armored scout cars had come along the coast road from yards near Ariake Bay and Kanoya.

The gravel road was in good condition but barely one good lane wide in stretches. It took some time to find our place toward the rear of the large company. We had time though. The mechanized column had five miles to cover. The infantry beside us had less distance to cover, but they had to go up and down almost as much as forward. We were to wait until a bit after noon, or the first time the infantry made contact, to shove forward.