[History repeats itself, sometimes only months apart.]

I entered one important looking tent and found staff officers huddled over local maps, noting positions of subordinate units and updating strength and supply tables for each. More senior officers were working around a smaller table. They had laid out another map, not of Kyushu, but of southern Okinawa. I was familiar with the area, from watching men train there. These officers knew it better, from watching men die there.

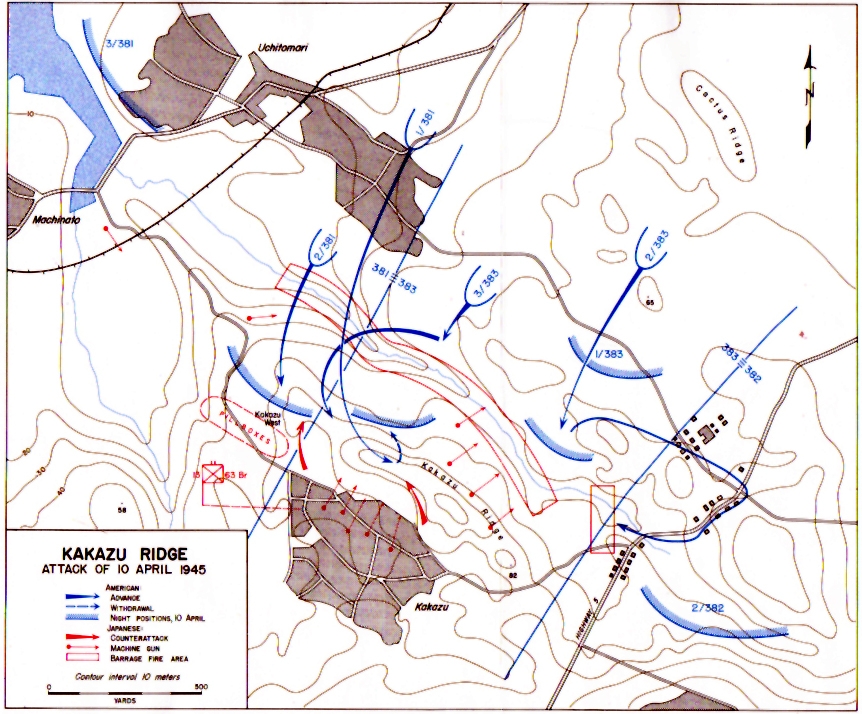

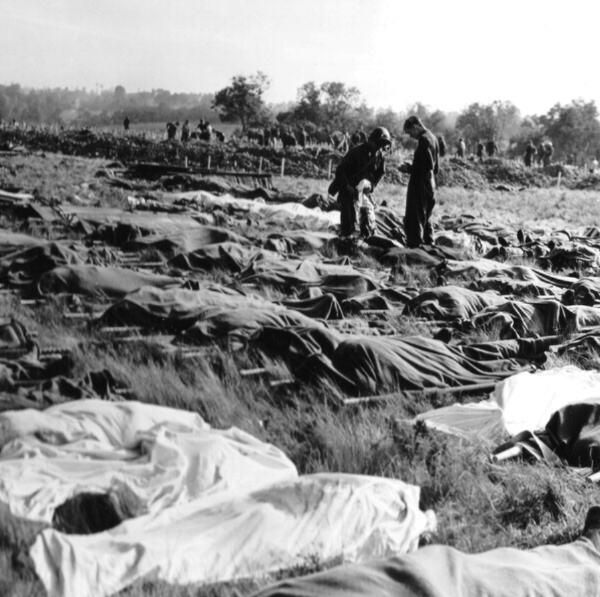

The 77th and the 81st infantry divisions had yesterday been repulsed, with tough losses. They were trying to jump from one line of anonymous hills and high paths over onto a larger set of named peaks and ridges. The 77th had tried the same thing on a smaller scale on Okinawa and also failed on the first several attempts.

Dead and injured were still being collected from yesterday, but the new attack would not wait. They were to go again this morning, with a new plan based on old lessons. Rain was predicted to continue for a third day, but that too was just like on Okinawa.

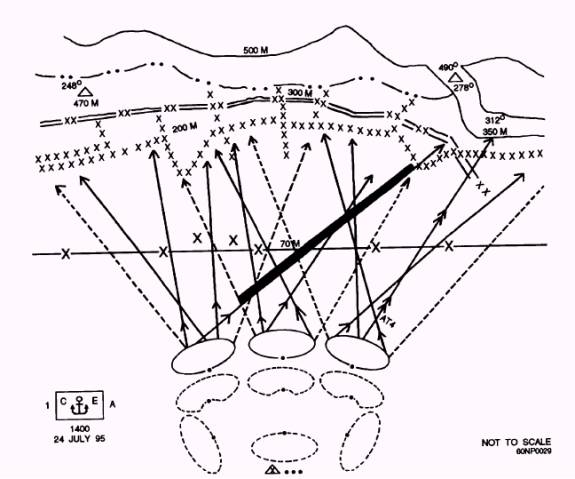

The Navy was called in to Kagoshima Bay to support with big guns. Once the attack started they would not fire on the mountainsides which our soldiers were attacking. They would plaster the reverse slopes, where it was expected Japanese defenders were only shallowly dug in. So long as they stayed hunkered down, American teams could work methodically through the valley between the two high lines.

Noise of the renewed assault was thick and loud by the time I went up with an observer from the headquarters unit. Engineers had worked through the last two days and nights to clear rough roads through and over the forested hills. Softer parts of the road were corduroyed with felled logs, brutal riding in a round-wheeled jeep. We came out onto one of the sharper peaks, dodging a hard working bulldozer to make the top.

Heavy tanks and larger self-propelled guns had been established on most such local peaks, owing much to extreme engineering effort. More than one had been left stuck, or had simply fallen right through the edge off of a waterlogged embankment.

Our tanks would be static guns for the day. They could depress their guns better than the heavy howitzers, firing directly down into the valley. Down in that valley mixed teams of tanks and liberally equipped infantry worked along the valley at a dead slow pace. They could rarely be seen.

Usually we could only track American progress by the smoke and dust made by their magnanimous application of firepower. When one of the smaller tanks came forward, there was no mistaking the sight of its long range flame thrower scorching a substantial patch of the mountain.

The opposing ridge was rugged and wavy, with many deep crevices in the near side. Each crevice was treated as a new objective, soldiers climbing up the near edge, before tanks turned into it as the men moved around the edge. Steady rain kept visibility short and footing haphazard.

Japanese guns waited for good targets and opened up only when the side of a tank or a cluster of men presented themselves, which was often. The Japs took a toll on the approaching soldiers and armor, often firing from close range where the covering guns on our side of the valley could not safely engage them. More than once the American GIs simply backed up and waited for friendly guns to pulverize the threat, before rushing the position with grenades and charges.