[Tuttle was as surprised as anyone at a large surprise attack across the I Corps front. he got up front again, getting a good look at the ‘busy beaver’ engineers.]

I learned about the operation only by chatting up another fellow down where hot showers had been set up near the river. Soap still in my ears I toweled off and jogged back into town in my week old dirty uniform. In short order I was hitching a ride further west on the back of an armored bulldozer.

On the dozer with me was a two-man chainsaw team and their two-man chainsaw. Corporal Vernon Starr, of Eugene, Oregon, informed me that Lumberjack is a real official U.S. Army specialty, job number 329 if you want to sign up. “They actually came out recruiting us, and it’s a good thing.” He didn’t look away as he thumbed toward the forest. I didn’t look either. It didn’t matter which way he pointed, there was nothing but forest filling every horizon and most of the sky.

“Normally we want to think ahead on a tree line. They have to come down a certain way, in a certain order, for the lumber picker to drag them back and get them to the mill. Out here they want us to fell them just one direction – the hell outta the way!” We are rolling through what the Japanese have designated a national forest. They are here to reduce it, more than just a little bit.

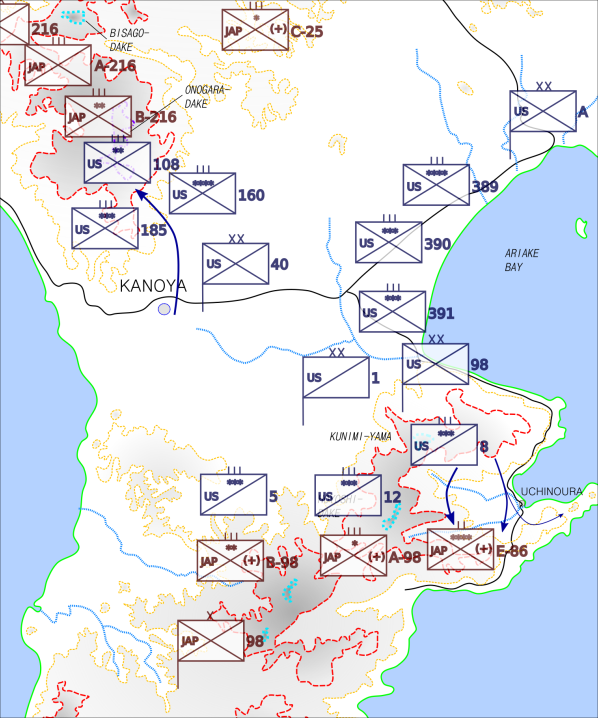

The forest between Miyazaki and Miyakonojo does not have hills and mountains as steep and high as in other places, but the hills run into each other with no order and no interruption. It is dense terrain and almost impossibly thick with tall evergreen trees. Other areas we had fought in had only a few roads and trails. The forest preserve had no roads at all, until now.

There are exactly two reasonable passes through the forest toward Miyakonojo. It was not surprising that the Japanese defended them, but the scale and stubbornness of the defense has been a big problem. Going around the forest proved unworkable, so now we are going through it.

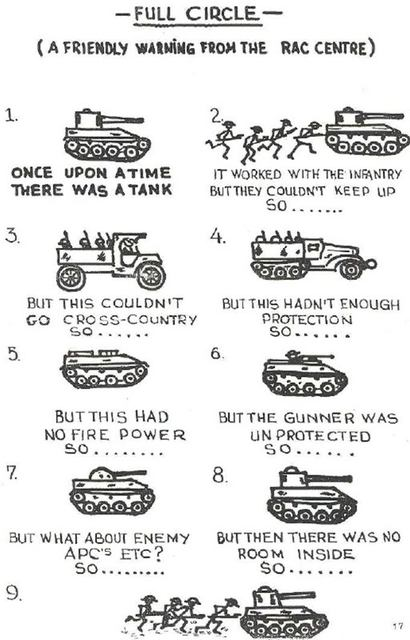

Engineers have been working since we first secured this part of the forest, and for some time while it was still contested, cutting roads through. Where they can manage it the roads run arrow straight, “To make shooting lanes if the enemy comes out at us.” Our dozer climbs and falls as we pass from one high spot to the next.

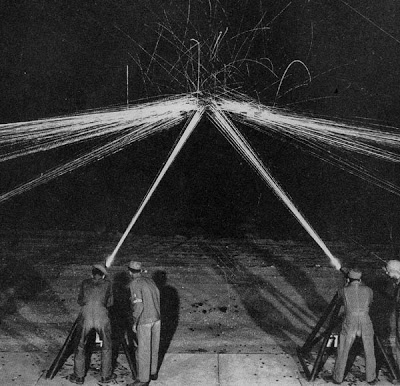

Most hilltops have a clearing with some kind of camp on it. We passed communications, kitchen, and medical groups in order until we got to the first combat units. A new artillery base was still being cleared as men bedded in a pair of our truck-size 155 mm guns , sisters to another pair not far away. Incredulous about how they got there, I asked. The answer was a derelict tracked tow vehicle shoved off to the side. Of the six tractors they used to bring up guns and shells, three of them were torn up and didn’t make it back. That one was abandoned in place up there on the hill.