[Skies cleared and Tuttle watched the attack on Sakura-jima gain a new dimension.]

Each spiny ridge must be taken in turn, but none of them are worth anything in isolation. The sharp top crease offers little safe ground to hold, and both sides can be fired on by the adjacent enemy held faces. There is little cover to use and no chance to dig positions into the bare rock. Every effort forward soaks up a great deal of manpower and firepower.

I was still observing from a high spot overlooking the island’s land bridge when an officer from a 1st Cavalry Division artillery unit joined me. Captain Condon Terry’s guns were somewhere on the shore of the island in front of us. He came back to “watch the show.”

In a slight north Texas drawl the captain told me what to watch for. “This is the only job going anywhere [on Kyushu]. The Army needs that rock taken out; it’s the last thing keeping us from pushing north.” He paused while a dense chevron of attack planes came in low overhead. “Here it is! It’s on now.”

The planes let loose volleys of large and small rockets, each pulling up and turning to the east as it got light. The rockets all impacted some ways up hill from a line of colored smoke being made by American troops. Before the rocket planes were out of sight regular bombers came across the line from the southwest, laying iron bombs into points higher up, including the main volcanic crater. Loose anti-aircraft fire tightened up as the formation passed. The very last plane, of about two dozen older B-17s, poured smoke from the left side for a mile as it slowed down behind the others. It tried to turn with the formation and that wing simply fell off into the bay. The rest of the plane joined it just short of the American held shore.

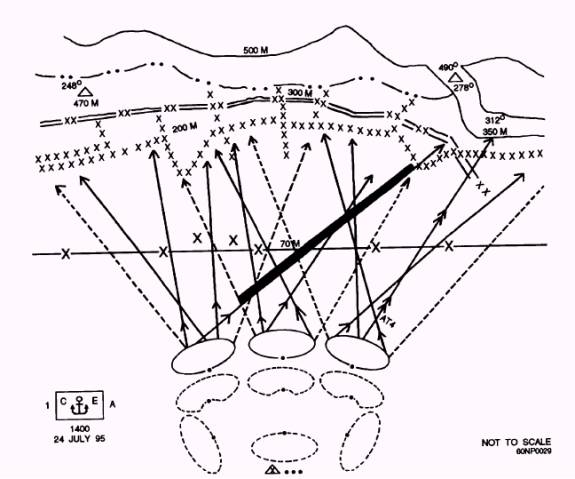

Captain Terry was still enthusiastic about the display. “That’s going to happen every two hours on the dot, so long as weather holds.” He checked his watch. “They’ll give it another four minutes for smoke to clear then my artillery will start working the hill. Twelve minutes after that, everybody advances, the Marines too.”

As he called it, guns below us barked out fresh ranging shots. I heard louder booms to the left and looked to see Navy destroyers and a couple cruisers in the bay. They were not about to miss this party. “Everything is pre-set and timed out,” the captain continued. “There’s naught for me to do but sit back and watch. An artillery man doesn’t hardly ever get to see his own work!”

Late in the afternoon one of the Navy LSTs which had been used weeks ago as a temporary beach-front hospital ship was moved to a small dock on the southwest corner of Sakura-jima. Army and Marine Corps units had met there this morning, including engineers. The small floating hospital was full to capacity as quickly as it could be loaded. The engineers were still clearing space and setting up a large aid station. Scattered harassing artillery fire reminded the engineers and doctors that their position was still at risk, but it didn’t look like it had been singled out by Japanese spotters.

Our own observation planes several times have caught small boats bringing supplies or reinforcements to the north side of Sakura-jima. Everyone is reminded that taking the island volcano quickly is tantamount to taking it at all.