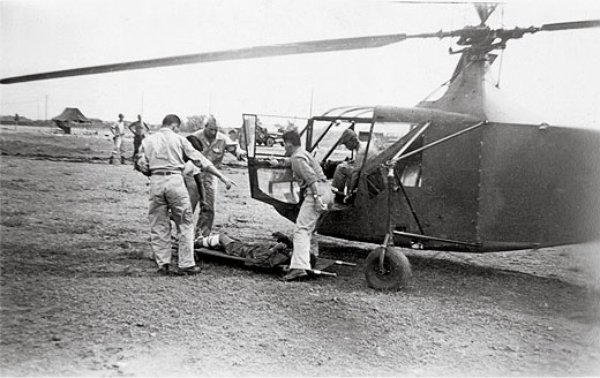

[Tuttle went along with a medical team on its way to reinforce the exhausted doctors on Tanega-shima.]

A call went out for volunteers on clean calm hospital ships to go get dirty for a while. Lead nurse Chief Evan Fields tells me half the ship volunteered, so this group was chosen by lottery. The group of seven is from eight different states, spanning the continent from Maine to Oregon. Pharmacists Mate Paul Atha was born on a Kiowa reservation nineteen years ago in Oklahoma. We sang him happy birthday over the sound of our ship’s engine.

Each person in the medical team had a heavy foot locker with him, and other boxes and crates, all barely luggable by one man. I needled them about their excess baggage but Dr. Federowicz corrected me. “All we have with us is the clothes on our backs. They’ve been tearing through medical supplies on the island, so we brought our own tools and all the consumables we could carry.”

Our ship tied up at a temporary pier off the south end of the American beach head. It was supposedly the safest place on the still hotly contested island. I unloaded crates for the team, as they were put to work immediately loading injured soldiers onto another boat. I followed bedraggled corpsmen and stretcher bearers to the aid station the stretchers were coming from. Their dirty green uniforms were damp with sweat in the mid afternoon sun. Just that morning they had been dry for the first time in days.

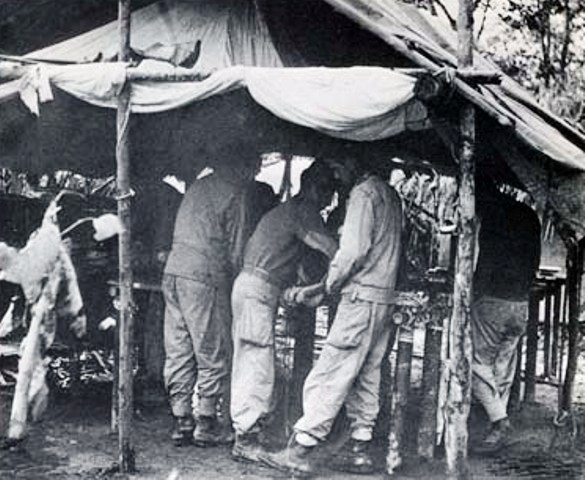

The aid station is nothing more than three twelve foot square tents. Under clear warm skies the tent flaps are wide open. One can watch four teams of surgeons working two of the tents, wading through loose bundles of dirty uniform pieces and bloody gauze on the ground at their feet. As I passed stretcher bearers took one case off the last table, carting him over to a quiet corner of the loosely organized compound. There laid rows of poncho covered bodies, some with a stake at the head holding some memento left by comrades who were still standing. Stretchers were in short supply and not left with the dead.

For a moment the bustle and flow of the scene reminded me of a casino with popular table games. Gamblers come in and out, each trying his luck. The doctors and nurses are just dealers and croupiers, they have no stake in the game, however they might cheer for the lucky and anguish over the losers. The House is death itself, and the house is doing terribly well, paying out absolute loss to losers but only meager victories to the winning gamblers.

The surgeon from that losing table stepped out into the sun, resting his weight on his knees for a moment, staring passively at the well worn dirt trail in front of his work place. After a routine cleaning of the operating table corpsmen brought another priority case into the tent. The surgeon joined his team in the third tent to change his apron and gloves and move on to their next case.