[Tuttle shuttled over to visit another island off Okinawa while everyone else packed up for the impending invasion.]

I wanted to visit Ie Shima for a particular, perhaps peculiar, reason. It is a small island with a small mountain and a small airfield, which the Army took with some cost, and many more Japanese died defending it. The same can be said now for many dozens of small islands in the Pacific. Ernie Pyle died here.

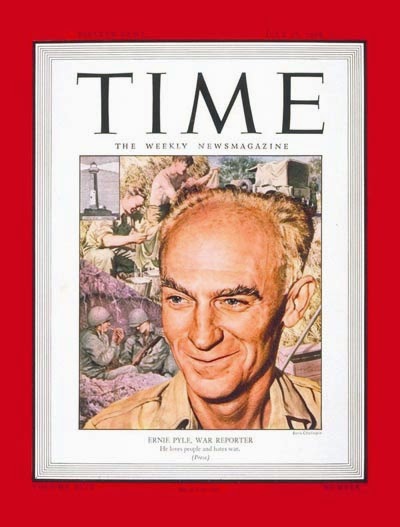

If you are reading this column you are probably aware of Ernie Pyle’s enormous legacy. If you are reading this column instead of his, you probably also miss him. I read that Pyle was read in over 700 newspapers by 40 million people. I’ve no way of researching the point right now, but I can’t imagine a writer in the past has ever had so wide a circulation or readership. This was at a time when newspapers may be just past their peak of power, as newsreels and radio broadcasts are taking a growing share of attention. Pyle may go down as the most widely read reporter and one of the most influential men of his day. Pyle would have wanted nothing to do with any such power.

Pyle made his name by learning about everyday Americans and sharing their stories. Tire treads and shoe leather were never spared as he criss-crossed the continent finding the big little stories that make us up. There was really nothing different about doing that on other war-infested continents. The subjects were living in the ground and getting shot at, but they were living just the same, each with an American story to share.

If you’ve ever felt empathy for a dirty cold soldier 5000 miles away, where you could really feel the chill in your bones as you reflexively scrunch your own shoulders to shrink down into a hole in the earth to hide from exploding artillery shells, it was probably because of Ernie Pyle. If you’ve felt the anxiety of an air base ground crew counting their damaged planes coming back from a raid, and the empty gut that comes when the count is short, it was probably because of Ernie Pyle.